Timeline

Previous article Sep 30, 1961 • Paul McCartney and John Lennon travel to Paris

Concert Jan 22, 1962 • United Kingdom • Liverpool • Lunchtime

Concert Jan 22, 1962 • United Kingdom • Southport • Evening

Article Jan 24, 1962 • The Beatles sign a management contract with Brian Epstein

Concert Jan 24, 1962 • United Kingdom • Liverpool • Lunchtime

Concert Jan 24, 1962 • United Kingdom • Liverpool • Evening

Next article Mar 17, 1962 • The Beatles attend Sam Leach and Joan McEvoy's engagement party

Related people

Related articles

On this day, The Beatles signed a contract to make Brian Epstein their manager, just a few weeks after he’d first seen them play live at the Cavern. Being under the age of 21, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Pete Best had to have the legal consent of their parents to enter into a contract.

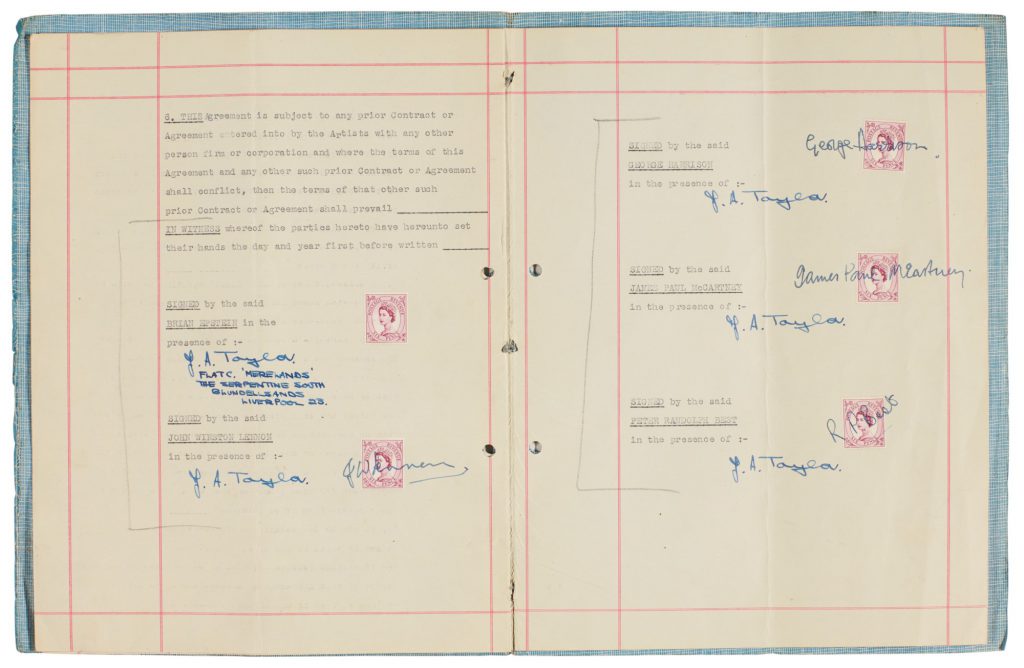

Typescript management contract between Brian Epstein “(hereinafter called ‘the Manager’)” on the one part, and John Winston Lennon, George Harrison, James Paul McCartney, and Peter Randolph Best “(hereinafter called ‘the Artists’)” on the other part, SIGNED BY ALL FOUR BEATLES,

comprising six clauses, numbers two and three with multiple sub-clauses, each member of the group signing over a 6 d. postage revenue stamp, and each signature witnessed by Epstein’s personal assistant Alistair Taylor (“J.A. Taylor”), 7 pages, folio (281 x 227 mm), 24 January 1962, stab-stitched with green ribbon in original blue paper wrappers docketed on the lower cover by the solicitor’s office (“Dated this 24th day of January 1962 | Brian Epstein | and | ‘The Beatles’ | Agreement | Silverman, Livermore & Co., | Solicitors, | Liverpool.”), scattered later pencil markings, punch-holes, light staining to wrappers

[with:] translation of The Beatles 12-month production agreement with Bert Kaempfert Produktion of Hamburg of 1 July 1961, carbon copy typescript, 8 numbered pages, large post quarto (250 x 205mm), the translation dated “HCR 5.12.1961”, punch holes, spotting

“…The Artists are desirous of performing as a group of musicians to be known as “THE BEATLES”…”

THE BEATLES ORIGINAL MANAGEMENT CONTRACT WITH BRIAN EPSTEIN. It is inconceivable that The Beatles could have achieved all that they did without Brian Epstein: it took more than inspired musicianship and song-writing to remake popular music, and the presentation, direction, and internal harmony of the Beatles all owed a huge amount to their manager. He was, as Paul McCartney has acknowledged, the Fifth Beatle. “We loved him”, said John, “and he was one of us”; his sudden death in 1967 was a huge loss and without him the band began to disintegrate.

This key relationship began some two and a half months before the current contract was signed, on 9 November 1961, when a smartly-dressed businessman “arrived at the greasy steps leading to the vast cellar and descended gingerly past a surging crowd of beat fans” into the Cavern Club on Liverpool’s Mathew Street, “as black as a deep grave, dank and damp and smelly” (Epstein, A Cellarful of Noise (1964), p.46). Brian Epstein came to hear a local band and to ask about their solitary recording, ‘My Bonnie’ (recorded in Hamburg with The Beatles as backing to the singer Tony Sheridan), which had begun to be requested in his record shop. He was immediately caught by the powerful thrill that had buzzing fans queuing outside the Cavern for The Beatles lunchtime gigs: the energy of their music, the sexual charisma, and the charm and wit with which they engaged with their audience. He had no experience of music management, but from the very first time he heard their sound Epstein was determined to be the manager of The Beatles.

For Epstein, managing The Beatles was a passion not a calculated business decision. Epstein always believed that their extraordinary combination of musical talent and charisma could lead the Beatles to be “Bigger than Elvis”, but there were deep personal reasons behind his desire to involve himself with the group: he saw an opportunity to be part of something new, to do something more creative than manage a record shop, and he quickly developed a crush on John. Epstein entered their lives when The Beatles were in danger of losing momentum. The band had returned from their second stint in Hamburg in July 1961 having lost one of their members, Stuart Sutcliffe, but having made their first recording. They were pre-eminent in the Liverpool music scene and drew crowds in Hamburg’s Reeperbahn, but they were unknown elsewhere, struggled to find gigs at new venues, and were gaining a reputation for bad behaviour: when Epstein spoke to Allan Williams, the band’s previous manager, his advice was “Brian, don’t touch them with a fucking bargepole” (Mark Lewisohn, All These Years: Tune In: Extended Special Edition (2013), p.1005). Nevertheless, Epstein pitched his services to the band less than three weeks after he first heard them play, and in that short period he had already begun talking to record industry contacts to arrange auditions. The Beatles rolled into Epstein’s shop, NEMS, late for their meeting with Epstein on 29 November. The shop was only a couple of hundred yards from the Cavern but they had stopped at a pub on the way. He quickly impressed the band with his obvious passion for their music and belief in their talent; his combination of honesty, class, and wealth; and his experience in running Liverpool’s best record shop, which gave him industry contacts that he was prepared to use in their favour. A few days later the band made their unanimous decision and John gave Epstein his answer: “Right then, Brian. Manage us, now. Where’s the contract? I’ll sign it.” (Epstein, p.51)

There was a problem: “I had no idea what a contract even looked like and I didn’t think it would be sensible to take the signatures of four teenagers on any old piece of paper” (Epstein, pp.51-53). He believed in “the boys” and took a great deal of attention to ensuring that his contract with them was professionally drafted and that its terms were fair. A preliminary Heads of Agreement was sketched in a meeting with Keith Smith, the Beatles’s accountant, on 6 December 1961, and Epstein also obtained a sample contract from one of his record industry contacts. The contract was then drafted by David Harris of the local legal firm Silverman, Livermore & Co., who later recalled how Epstein was “very keen indeed to ensure that the contract was a fair one” – it was certainly much more generous to the artists than the industry sample on which it was based. It took several weeks before Epstein was happy with the wording. When the group gathered on 24 January, by some accounts in Pete’s mum’s front room, the contract that was placed before them was in its third draft. The contract gave Epstein responsibility not only for finding the band work, and managing their schedule, but also for publicity and “all matters concerning clothes, make-up and the presentation and construction of the Artists’ acts and also on all music to be performed” (not that Epstein, or anyone else for that matter, ever had much success in telling The Beatles what they should play). In return, his fee was to be 10% rising to 15% if their earnings should exceed £120/week (Paul negotiated the upper percentage down from 20%).

Whilst this contract bound Epstein to the Beatles, it did not bind The Beatles to Epstein. He chose not to sign the contract, and Taylor, Epstein’s PA who witnessed the contract, later wrote that “The mood in the room changed suddenly, from mounting excitement and glee to confusion and anxiety”, when it became clear that the space for Epstein’s signature would remain blank (quoted Lewisohn p.1066). Epstein explained himself in his autobiography:

“It was because even though I knew I would keep the contract in every clause, I had not 100 per cent faith in myself to help the Beatles adequately. In other words, I wanted to free the Beatles of their obligations if I felt they would be better off.” (Epstein, p.59)

He need not have worried. In 1962, under Epstein’s management, The Beatles were transformed into the band that would conquer the world. He encouraged them to take a more professional attitude to their work. He emphasised that if they wanted promoters to rebook them, they had to be punctual; he stopped them from eating and drinking on stage; he encouraged them to bow to the audience. The distinctive early Beatles haircut pre-dated Epstein, but he got them regular appointments with his hairdresser to ensure their mops were properly styled. He also got them out of leathers and into sharp, Italian-style tailored suits. John in particular would later complain that the suits were a sell-out, but they simply weren’t going to get bigger bookings unless they smartened up. Anyway, as John himself admitted: “Everybody wanted a good suit – a nice, sharp, black suit … We allowed Epstein to package us, it wasn’t the other way around” (Lewisohn, p.1082).

Epstein struggled for several months to get The Beatles a recording contract. He not only faced metropolitan condescension towards a Northern provincial act, but also incomprehension about the group set-up and especially its alternating lead singers. The translation of The Beatles recording contract with German bandleader and producer Bert Kaempfert, which forms part of the current lot, was the first outcome of Epstein’s work on signing The Beatles to a label. If Epstein was going to sell his band to a record company he needed to know the exact terms of their existing contractual arrangements, so he took the German contract with him when he met his friendly contact Ron White, marketing manager at EMI, on 1 December 1961 (this was the meeting that Epstein had promised the band when he pitched his services to them on 29 November). White agreed to help Epstein (NEMS was a good client and White had respect for its manager) and within days the contract was translated by EMI and posted back up to Epstein along with a letter from White assuring Epstein that its terms need not impede a new contract with a British label and promising to bring The Beatles to the attention of EMI’s A&R division (see Lewisohn pp.1006 and 1034). However this initial approach to EMI soon stalled, and then The Beatles were rejected by Decca, who opined to Epstein that “we don’t like your boys’ sound. Groups of guitarists are on their way out” (Epstein, p.55). Decca would thereafter be saddled with being the label that turned down The Beatles, but the band had got a test recording out of the encounter and this proved to be a considerable help to Epstein in the following months. Eventually, on 9 May, Epstein met George Martin of EMI’s Parlophone label at their recording studio on Abbey Road and was told that The Beatles would be offered a recording contract. Epstein always pushed the fact that the band wrote some of their own material, and it was the potential publishing income from these songs that whetted the appetite of EMI more than the band’s likely record sales.

The recording contract was a huge breakthrough, of course – and in signing with George Martin The Beatles proved to be as fortunate with their producer as they were with their manager – but the subsequent recording session on 6 June brought into focus another problem: Pete Best’s technical limitations as a drummer. George Martin’s damning verdict on the percussion in their first Parlophone recordings confirmed what they already knew, indeed George Harrison had been manoeuvring to replace Pete with the more experienced (and more extrovert) Ringo Starr for some months, but it forced them to act. Or, to be precise, it pushed John, Paul and George to force Brian Epstein to act. It was Epstein who rang Ringo at Butlins in Skegness, where he was playing for the summer, to invite him to join The Beatles; and it was Epstein who met with Pete to tell him he was out.

The January contract did not cater for any change in personnel, so with Pete’s replacement by Ringo it became void. Also, according to the contract, Epstein was still obliged to find employment for Best, so he duly found a place for him in another band (Epstein had, by now, begun to manage other Liverpool acts). On 16 August he wrote to the lawyer David Harris and instructed him to draw up a new contract, with Ringo replacing Best. The current contract contains scattered pencil markings where Harris used it to prepare the new contract. Harris and Epstein also took the opportunity to rectify a flaw in the earlier contract, which was that since Paul and George were under 21 they should have signed alongside a parent, and to increase Epstein’s fees to a maximum of 25% on earnings above £200/week. This second contract, which was to remain in force until Epstein’s death, was signed by Epstein and the band on 1 October 1962. It was sold in these rooms in 2015 (29 September 2015, lot 42, £365,000).