Details

- Born: Feb 06, 1956

From Wikipedia:

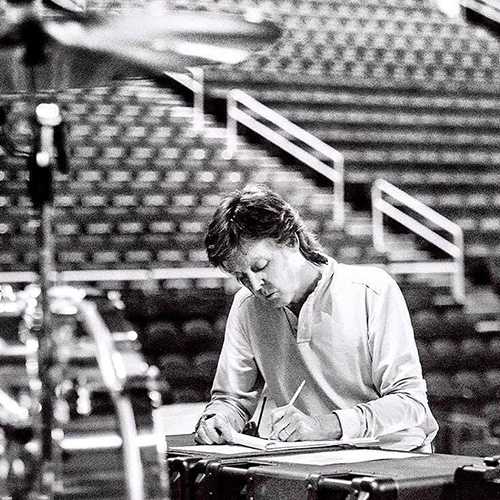

Jerome David “Jerry” Marotta (born February 6, 1956 in Cleveland, Ohio) is an American drummer currently residing in Woodstock, New York. He is the brother of Rick Marotta, who is also a drummer and composer.

Marotta was a member of the bands Arthur, Hurley & Gottlieb (1973–75) Orleans (1976–77 & 1982), Peter Gabriel’s band (1977–86), Hall & Oates (1979–81), the Indigo Girls (1991–99), Stackridge (2011), Sevendys (2010–present) and The Tony Levin Band (1995 to present).

Marotta also played drums on Stevie Nicks and Mike Campbell’s song “Whole Lotta Trouble” from Nicks’ 1989 album The Other Side of the Mirror. He has also performed on albums by Ani DiFranco, Sarah McLachlan, Marshall Crenshaw, The Dream Academy, Suzanne Vega, Carlene Carter, John Mayer, Iggy Pop, Tears for Fears, Elvis Costello, Cher, Paul McCartney, Carly Simon, Lawrence Gowan, Ron Sexsmith, Banda do Casaco, Joan Armatrading and many others. […]

Jerry Marotta contributed to McCartney’s 1986 album, “Press To Play“.

[Producer Hugh Padgham] mentioned Jerry Marotta, he mentioned Phil [Collins] as well, but I didn’t want to get Phil too heavily involved because of the risk of people saying ‘Oh you’re just going for flavour of the month’, and I really wanted a drummer to do the whole album. I knew Jerry’s work from Peter Gabriel and Tears For Fears, and Hugh recommended him as a good thwacker of a skin!

Paul McCartney, Club Sandwich N°42, Autumn 1986

From an interview in Modern Drummer, March 1986:

Interviewer Robyn Flans: How did you get called for the McCartney gig?

Jerry Marotta: Through Hugh Padgham, an engineer/producer who did the last couple of Police records, the Bowie record, Phil Collins, and Genesis. He had engineered a Peter Gabriel record, which is how we met. He called me in January of 1984 and asked what I was doing next April. He said that he couldn’t tell me what it was because it wasn’t definite, but that it was something very big. Then he called me about six weeks later, and told me he was producing McCartney and he wanted me to do it.

RF: What was that like?

JM: It was an interesting experience working with somebody like Paul McCartney, who is certainly the most successful working musician alive.

RF: Why?

JM: Because I’m interested in being a Paul McCartney myself—a songwriter and more of an artist. So it was nice to work with the most successful composer of modern times.

RF: He’s also a drummer.

JM: He kind of plays the drums. He might be able to play the drums on a record, but just about anybody could play the drums on a record because of the wonders of modern technology. To have him play a live gig would really be the true test. I couldn’t see him doing that at all. But he’s got very good ideas as a drummer, and he’s a lovely guy. I respect him and his family. His prime concern is his wife and his children, which I love about him.

RF: In that situation, did you feel like a sideman?

JM: Definitely. I felt a little uncomfortable. That’s a good point. I never really thought about what I didn’t like about doing that record, but there were a couple of times on that record that one person or another said to me, “You’ve got to do it this way, because that’s the way I want you to do it.” I don’t like that at all, and most people I work with wouldn’t say that to me.

From Drummer Jerry Marotta on Years With Peter Gabriel and Paul McCartney – Rolling Stone, July 26, 2023:

You play on a few So songs [Peter’s Gabriel Album], but you didn’t go on the tour and haven’t been with Peter since. What happened?

Ultimately, I always remained loyal to him. At that point, Peter, for some reason, didn’t remain loyal to me. First of all, the timeframe was set to work with Peter. After that, I was going to do a record [Press to Play] with Paul McCartney. But Peter shifted the time to the same time as the McCartney record. I didn’t feel like I could blow off the McCartney record. Not because he was Paul McCartney, but it was Hugh Padgham, who worked with Genesis and Peter. He was the one that got me on that. I was the only outside musician. It was Paul, Eric Stewart from 10cc, and me. Just the three of us. Bailing on it didn’t feel right to me. […]

You play on “Veronica” with Elvis Costello, right?

I do. That same year, I worked with Paul on Press To Play. Later that year, I ended up working on Spike with Elvis. When I was working with Paul, they were trying to find someone to kind of fill the shoes of John Lennon. Elvis Costello is the perfect candidate for that. Paul was saying, “They’re trying to get me to write with Elvis Costello, but it never pans out.” When I was working with Elvis, they co-wrote “Veronica” and a couple of other songs.

I said to him, “What happened? Paul told me this wasn’t panning out.” Elvis goes, “Jerry, first of all, I don’t co-write with anybody. I write my own songs. But they kept bugging me and bugging me. Eventually I thought, ‘I’ve got these songs kicking around that I’ve never been able to finish. I’ll send a couple of those to Paul. What do I have to lose? I’m not finishing them.’ I sent them to Paul, he worked on it, sent it back, and I really like what he did.”

Was it intimidating to record for McCartney?

Look, he’s Paul McCartney. I wasn’t a massive Beatles fan, but I could appreciate them. I know they were really good, of course. Again, it was Eric, Paul, and me. And Hugh. It was funny. Long before we recorded, his manager picked me up in London while I was working on another record. He drove me down to meet Paul since he wanted to meet me before we started work. He wanted to feel like we knew one another.

We’re playing a song, playing it again, and again, and again. I’m not used to that. I’m used to getting the job done. We didn’t work long hours. His kids were all young and at school. The next day, we come in. We’re playing the same song again. I said to him, “Listen, if I’m not getting the job done, and you want to get someone else in…” I just couldn’t understand why we kept playing the same song. He goes, “Jerry, I’m not even thinking about a take. I just want to play.”

It’s kind of what made the Beatles. It was like a band thing. You play it and play it and play it. Some of them needed to do that. I didn’t. I knew how to come up with a drum part pretty quickly. He goes, “Jerry, you’re doing a great job. I’m loving it. Let’s just relax. I haven’t made a record in five years. I haven’t really been playing. This is what I want to do, have fun, relax, play.”

And so every song we did took three days to record. Then they figured which one they wanted. I fell into that groove. It was awesome. He was great to work for. […]

By the way, when the McCartney record came out [Press to Play, in 1986], it tanked. It was really not fashionable to be Paul McCartney at that time. There was this whole thing about how “Lennon was at the real talent.” Lennon, of course, was what he was. But Paul McCartney is just a straight-ahead working-class musician. He writes songs like “The Long and Winding Road” and “Yesterday,” but he also writes “Silly Love Songs,” “Ebony and Ivory,” and “Say Say Say.” He just writes what he writes. He writes whatever he’s feeling. It was not well-received.