From Wikipedia:

Robert Fraser (13 August 1937 – 27 January 1986), sometimes known as “Groovy Bob”, was a London art dealer. He was a figure in the London cultural scene of the mid-to-late 1960s, and was close to members of the Beatles (particularly Paul McCartney) and the Rolling Stones. In February 2015, the exhibition A Strong Sweet Smell of Incense: A Portrait of Robert Fraser, curated by Brian Clarke, was presented by Pace Gallery at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. […]

Career

After a period spent working in galleries in the United States he returned to England, and with the help of his father (a wealthy financier who had also been a trustee of the Tate Gallery) established the Robert Fraser Gallery at 69 Duke Street (near Grosvenor Square), London, in 1962. The gallery interior was designed by Cedric Price.

The Robert Fraser Gallery became a focal point for modern art in Britain, and through his exhibitions he helped to launch and promote the work of many important new British and American artists including Peter Blake, Clive Barker, Bridget Riley, Jann Haworth, Richard Hamilton, Gilbert and George, Eduardo Paolozzi, Andy Warhol, Harold Cohen, Jim Dine and Ed Ruscha. Fraser also sold work by René Magritte, Jean Dubuffet, Balthus and Hans Bellmer.

“Swinging Sixties”

In 1966, the Robert Fraser Gallery was prosecuted for staging an exhibition of works by Jim Dine that was described as indecent (but not obscene). The works were removed from the gallery by the Metropolitan Police, and Fraser was charged under a 19th-century vagrancy law that applied to street beggars. He was fined 20 guineas and legal costs.

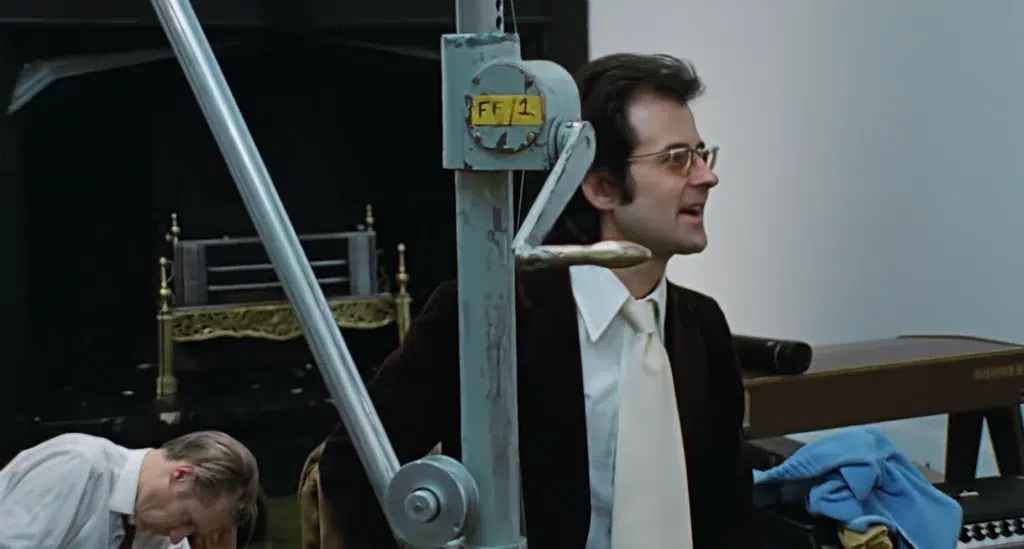

Fraser became a trendsetter during the Sixties; Paul McCartney has described him as “one of the most influential people of the London Sixties scene”. His London flat and his gallery were the foci of a “jet-set” salon of top pop stars, artists, writers and other celebrities, including members of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, photographer Michael Cooper, designer Christopher Gibbs, Marianne Faithfull, Dennis Hopper (who introduced Fraser to satirist Terry Southern), William Burroughs and Kenneth Anger. Because of this, he was given the nickname “Groovy Bob” by Terry Southern. His flat at 23 Mount Street, on the third floor above Scott’s restaurant, was described by Barry Miles as one of the “coolest sixties pads in London”.

Fraser art-directed the cover for the Beatles’ 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band – he dissuaded the group from using the original design, a psychedelic artwork created by the design collective The Fool, instead suggesting the pop artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth, who created the famous collage cover design for which they each won a Grammy Award.

It was through Fraser that Richard Hamilton was selected to design the poster for the White Album. His gallery also hosted You Are Here, Lennon’s own foray into avant garde art during 1968.

He was a close friend of the Rolling Stones and was present at the infamous 1967 party at Keith Richards’ country house, Redlands, which was raided by police, leading to the subsequent arrests and trials of Mick Jagger, Richards, and Fraser on drug possession charges. The event is commemorated by the 1968 Richard Hamilton artwork Swingeing London 67, a collage of contemporary press clippings about the case, and the portrait of Jagger and Fraser handcuffed together also entitled “Swingeing London”.

Fraser always insisted that neither Jagger nor Richards actually had any drugs with them, and that everything found by the police actually belonged to him. During the raid he persuaded the officers that his 20 heroin pills were actually for an upset stomach and offered them only one for testing. Although Jagger and Richards were acquitted on appeal, Fraser pleaded guilty to charges of possession of heroin, and was sentenced to six months’ hard labour. After his release Fraser’s interest in the gallery declined as his heroin addiction grew worse, and he closed the business in 1969.

Fraser moved down the street to a large 8-room apartment on the 2nd floor of 120 Mount Street; the previous occupant was writer and theatre critic Kenneth Tynan. Keith Richards from the Rolling Stones was living with Fraser at the time, and it was here, sitting by the window in the lounge room, that Richards had the inspiration for the song Gimme Shelter

“I had been sitting by the window of my friend Robert Fraser’s apartment on Mount Street in London with an acoustic guitar when suddenly the sky went completely black and an incredible monsoon came down. It was just people running about looking for shelter – that was the germ of the idea. We went further into it until it became, you know, rape and murder are ‘just a shot away’.”

1970s and 1980s, and death

Fraser left the UK and spent several years in India during the 1970s. He returned to London in the early 1980s and opened a second gallery in 1983, with a show of paintings by the stained glass and architectural artist Brian Clarke, but by this time he was suffering from chronic drug and alcohol problems and the gallery never replicated the success of its predecessor, although Fraser was again influential in promoting the work of Clarke, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring.

It soon transpired that Fraser was also suffering from AIDS. He was one of the first ‘celebrity’ victims of the disease in the UK.

In 1985, he sold his Cork Street gallery to Victoria Miro, who subsequently created the successful Victoria Miro Gallery. Fraser seemed disillusioned, and told her at the time “You’ll never make a contemporary art gallery work in this country.”

He was cared for by the Terence Higgins Trust during his final illness and died in January 1986. He died at his mother’s flat in London.

For me and many others, Robert Fraser was one of the most influential people of the London sixties scene.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

The Apple label was for the Beatles’ music. But there was an undercurrent where John met Yoko [then an experimental artist] and I hung out with Allen Ginsberg. Andy Warhol came to my house and showed his film Empire there because I was the only one with a 16mm projector. A key figure was Robert Fraser who was the ringleader of this underground scene through his art gallery.

Paul McCartney – Interview with The Guardian, November 2008

[Robert Fraser] was, as Christopher Gibbs put it, ‘A principals only person, a star fucker.’ Robert was never interested in the entourage or the people who actually did the work, it was the famous person or the wealthy person who received the full blast of his charm. He was a crook and a snob, but fascinating and entertaining. We spent many amusing evenings with him nightclubbing, usually with Paul McCartney, during which we would inevitably show up just as a club was closing and Robert would have to bribe our way in, bending double in his skin-tight pink suit to pull huge wads of cash from his trouser pocket to give the doorman.

Barry Miles – From “In The Sixties“, 2003

Paul McCartney met Robert Fraser circa 1965, early 1966, and they would remain friends till Robert’s death in 1986. In April 1966, the two of them travelled to Paris for Paul to buy some Magritte paintings.

I would have met Robert in the early days of his gallery, and I suspect it was just by going into his gallery, which I often used to do. As a frequent visitor, I started getting invitations to previews and I’d stand around and meet the art crowd of that time. Anyway, I went to Robert’s gallery, we started to chat, and then I would often visit him at his flat. Robert’s flat was like a second gallery. He had a lot of Dubuffet around that he was trying to sell. I wasn’t too interested in him. He had a lot of stuff by Paolozzi, and I bought a big chrome sculpture which was called Solo, which was in the big Pop Art exhibition they had about two years ago at the Tate. I just said, “What is that, Robert?” Fantastic. He said, “What is it? I don’t know. It’s a mantelpiece, a bit of a car, who knows?” I was very happy with that attitude, not too academic. There was no dour art talk. It was much more razzy, loose, lively discussion with him. He was the best art eye I’ve ever met.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

Between 1966 and 1967, Paul acquired another painting by Magritte through Robert Fraser: a green apple overlaid with the text “Au Revoir,” titled “Le Jeu De Mourre.” This painting inspired the logo of Apple, the company recently launched by The Beatles.

Robert Fraser was this gallery owner – the guy who got busted with The Stones. He’s a great guy, he died a few years ago, he was great. He was brilliant and I bought a couple of these Magritte paintings through Robert – dirt cheap. We didn’t think he was going to be famous one day. In fact I now think he’s the best surrealist. Certainly didn’t think he’d ever be that. He was just one that we all liked – the skies, the doves and the bowler hats. Robert’s greatest conceptual thing he ever did, it’s like a scene out of a movie for me, was, it was one of these long hot kind of summers and I had a big back garden in St John’s Wood and we were all playing in the back garden, sitting amongst the daisies, and he didn’t want to break in on our scene. So he arrived and when we got back in he’d gone, but he’d left a painting just as we came through the back door, just on the table. It was a Magritte painting with an apple which we used for the Apple thing. That’s where we got the Apple insignia, this big green apple. And written across the apple were the words ‘Au Revoir’, like a calling card.

Paul McCartney – From “The Paul McCartney World Tour” book – 1989

In my garden at Cavendish Avenue, which was a 100 year-old house I’d bought, Robert was a frequent visitor. One day he got hold of a Magritte he thought I’d love. Being Robert, he would just get it and bring it. I was out in the garden with some friends. I think I was filming Mary Hopkin with a film crew, just getting her to sing live in the garden, with bees and flies buzzing around, high summer. We were in the long grass, very beautiful, very country-like. We were out in the garden and Robert didn’t want to interrupt, so when we went back in the big door from the garden to the living room, there on the table he’d just propped up this little Magritte. It was of a green apple. That became the basis of the Apple logo. Across the painting, Magritte had written in that beautiful handwriting of his ‘Au Revoir’. And Robert had split.

I thought that was the coolest thing anyone’s ever done with me. When I saw it, I just thought: ‘Robert.’ Nobody else could have done that. Of course, we’d settle the bill later. He wouldn’t hit me with a bill.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

There’s a great story about that. I had this friend called Robert Fraser, who was a gallery owner in London. We used to hang out a lot. And I told him I really loved Magritte. We were discovering Magritte in the sixties, just through magazines and things. And we just loved his sense of humour. And when we heard that he was a very ordinary bloke who used to paint from nine to one o’clock, and with his bowler hat, it became even more intriguing. Robert used to look around for pictures for me, because he knew I liked him. It was so cheap then, it’s terrible to think how cheap they were. But anyway, we just loved him … One day he brought this painting to my house. We were out in the garden, it was a summer’s day. And he didn’t want to disturb us, I think we were filming or something. So he left this picture of Magritte. It was an apple – and he just left it on the dining room table and he went. It just had written across it “Au revoir”, on this beautiful green apple. And I tought that was like a great thing to do. He knew I’d love it and he knew I’d want it and I’d pay him later. […] So it was like wow! What a great conceptual thing to do, you know. And this big green apple, which I still have now, became the inspiration for the logo. And then we decided to cut it in half for the B-side!

Paul McCartney – Interview with Flemish Public Radio, 1993

Robert [Fraser – art dealer and friend] also brought me other interesting Magritte’s pictures over the years and one of them became the inspiration for the original Beatles Apple Records label: the big green apple was inspired by Magritte.

Paul McCartney – From Paul McCartney | News | New Feature: Paintings On The Wall – René Magritte (1898 – 1967), March 2015

I had this really great mate, he was the owner of a gallery called Robert Fraser and he really knew his art, so I could get advice from him. And I enjoyed looking at those René Magritte, Belgian painter, and he knew his dealer. So Robert said to me “do you want to come to Paris and we’ll have dinner with this dealer, he’s invited us?” I said, “yeah right”. It was funny because Robert was gay and I told some of my friends I’m going to Paris with Robert. They went “are you sure”. I said “I’m quite secure about my sexuality”. Anyway… And the guy’s name was Alexander Iolas. And so, we have dinner and everything, it was above the gallery, so we go downstairs in these little stairs. And there were all those great paintings. An he’s like, you know, someone who loves his work. And I could now afford to buy a couple. Now I couldn’t, I mean you know, they are like, wow. But they were like three thousand pounds and now they’re worth a bit more but, yes, that kind of started my love of art. And in all of that, I saw this Apple and what happened one day, Robert knowing I loved this, I was out in the background in London doing a little music video with Mary Hopkin actually and I was busy and Robert knew I was busy. So I came back in from the garden and he’d left this little painting, little oil by Magritte, propped up on the thing and he had left, he’d just gone so and then one of the painting was a green apple and written across within Magritte’s writing was “au revoir”. So that is the coolest most conceptual thing anyone’s ever done. So yeah that’s where it came from. So people say “why was the Apple”, because you know there was an Apple before Apple… It was “a is for Apple”, we just like that it was near the beginning of the alphabet. So on any list, it would come early.

Paul McCartney – From Paul McCartney in Casual Conversation from LIPA, 2018

In 1967, Paul McCartney went to Robert Fraser to discuss the artwork of the new Beatles’ album, “Sgt. Pepper.” Fraser dissuaded him from using the original design, a psychedelic artwork created by the design collective The Fool. Instead, he suggested the pop artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth, who created the famous collage cover design for which they each won a Grammy Award.

Robert used to come round to my house in Cavendish Avenue, which was my bachelor pad in the sixties. It was bit more of a salon really — everyone just came round, anyone stuck for somewhere to stay. And Robert would ring and say, ‘Do you want to go out to dinner?’ His day revolved around dinner. Once he’d got dinner set, everything else fell into place. So he’d come round and I’d play him all the new stuff we were making. He was interested to hear all the demos, then he’d move to a visual on it, which eventually came true on the Sgt Pepper cover. By that time we were firm friends.

So Robert and I would just sit around, chatting late into the night, and I’d come back from America one time with this idea for Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and the concept was we’d pretend that the Beatles were this band. That would liberate us from our egos, so we’d be able to approach a microphone and think, ‘This is not me doing a vocal, this is someone else.’ That was very liberating and I think the album echoes that. So Robert would get all this.

Robert represented to me freedom, freedom of speech, of view. Mainly he was the art eye that I most respected. He turned me on to a lot of good art, and he turned me off a lot of not so good art, which was very helpful. Robert was very instrumental in getting the Sgt Pepper cover together. He really became the art director on Sgt Pepper.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

I suggested that we all think of heroes that the members of Sgt. Pepper’s Band might have, which would help us fill in their imaginary background story. I did a couple of sketches of how the band might look and, as we made the album, we experienced a sense of freedom that was quite liberating. […] When we were done, I took my sketches and our ideas to a friend of mine, Robert Fraser, a London gallery owner who represented a number of artists. He suggested we take the idea to Peter Blake, and John and I had discussions with Peter about the design of the album cover. Peter and his then wife Jann Haworth had some interesting additional ideas and we all had an exciting time putting the whole package together.

Paul McCartney – From the “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” box set, 2017

We were commissioned to work on sketches for the Sgt. Pepper album cover. I painted a rough idea on paper in gouache, the final artwork to be done after approval. It was just an initial concept sketch but everyone assumed it was the final artwork and established elitist art dealer Robert Fraser rejected it; he preferred to promote an artist of his own stable and ultimately only my inner disk sleeve design was used. However, after all, the final “Sgt. Pepper” cover collage by Peter Blake turned out great!

Marijke Koger – From The Fool – From marijkekogerart.com, August 11, 2021

l used to talk about Eton to Robert and ask, ‘How was it?’ Because I went to a grammar school and was intrigued to meet someone honest from Eton. He told me about the fag system. I said, “Do you think it made you gay?” He wasn’t sure. But from the stories he told me, it would be conducive to gayness, just the whole idea of serving an elder boy, fagging for him. And I understand it went much further than that.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

Once or twice with Robert I said, “What’s that you’re doing? Coke?” I felt very lucky, because he introduced it to me a year before most people were doing it. That was ’66, very early. The film industry went mad on it a few years after that. I did a little bit with Robert, had my little phial, and the Beatles were warning me. I said, “Don’t worry. Johnny Cash wrote a song about it.” It didn’t seem too bad. I started to find, though, that I had a big problem with numbness in my throat. Some people quite like that, but I’d occasionally think I was dying. I thought, “I’m paying for this pleasure. I’ve got to get sensible here. This is not clever. I’m not actually enjoying this.” With pot, I could sit back and enjoy it and find some pleasure in it. But with coke, the first couple of months were fine, but then I started to think, “No, this is not too wonderful. I’m not in love with this.” So I got in and out of coke very quickly, was able to rise above it.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

A lot of mixed people were on the scene, a kind of aristocracy in which I’d put Robert as part of. He had his friends among the Ormsby-Gores and the Londonderrys. I didn’t get into that much. Mick and the Stones more. I got on OK with them, but they didn’t turn out to be my crowd.

We often did drugs together, that was the scene. We’d occasionally have some acid trips out at my house at Cavendish Avenue. That was the secure place to do it. The thing I didn’t like about acid was it lasted too long. It always wore me out. But they were great people to be around, a wacky crowd. My main problem was just the stamina you had to have. I never attempted to work on acid, I couldn’t. What’s the point of trying, love?

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

At the time, Robert was doing heroin and I was thinking, ‘I really shouldn’t, but go on, it’s Robert, give us a sniff.’ Luckily it didn’t do much for me. I’d rather have a joint. So Robert said, ‘Great, I won’t offer it to you again. It was expensive. If you didn’t like it, no point in giving it to you.’ I’d just say when asked to have some, ‘No, I don’t, thanks.’ Robert continued on with it. He was the one who said, “There’s no such thing as heroin addiction, you’ve just got to have a lot of money. The only problem comes when you can’t afford it.’ I took that with a pinch of salt. Much as I loved Robert, I didn’t listen to his every word.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

Robert wasn’t good with money. I lent him bits of money that I didn’t see back. The way I looked at it, he’d actually made me so much money with some of the paintings he’d helped me get that it didn’t matter. We didn’t have to dot the i’s and cross the t’s. I figured I’d won financially. Not that it was a competition, but he certainly made me a lot more money than he lost me. But he did have a bad reputation with money.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

Robert could play the academic game quite easily, he was very knowledgeable, but I think he found it a bit boring. It wasn’t our scene, being academic. I’ve heard him hold his own with academics, but that wasn’t the buzz. The buzz was more of a mixture, a cross-over with musicians, etc.He turned me on to quite a few things, quite a few artists. We went down once on an impulse to see Takis, the great sculptor who did things with tank aerials with little lights on the end. That sort of thing was great. We’d just turn up at someone’s studio, smoke a bit of pot, sit around and just chat art.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

There wasn’t that much action in the [Andy Wahrol’s film] Empire State Building. And we just sat around with a bunch of friends, and Andy was very enigmatic, didn’t say more than two words: ‘Nice room. Thank you.’ Then we ended up going to the Baghdad House, which was the only place we knew of in London where you could smoke hash downstairs. We sat around this long table and ordered up various little couscous things. I never really talked to Andy though. But it was great fun and I thanked Robert for engineering thosemoments.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

There were many good times in Robert’s flat. Through my Beatle connections I’d hire a 16mm projector for the evening — I remember Ringo showing Jason and the Argonauts endlessly — and I started off with Wizard of Oz. Robert got into this, wow, and he’d get some art movies. We got a lot of Bruce Conners, showed a lot of that. It was a very exciting period.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

Robert was a good friend of Andy Warhol’s and when Andy came over he said, ‘Can we hire a projector and show one of Andy’s films?’ Paul Morrissey really made the movies — he was quite a good friend too.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

I was with Andy at the Cannes Film festival in 1967. We connected with Robert in London right away – he was really nice. We had the print of Chelsea Girls with us when we got to London. We’d taken it to Cannes to show at the Film Festival, and there were so many reels and it was so expensive that we’d taken it in our luggage. […] But they never screened it. They had announced it, it was part of the programme, but they hadn’t given it a date. They didn’t know how to screen the film. They needed two projectors and two screens, and I had to try and show them how to do it.

Then they were afraid there’d be some scandal because of ten seconds of male nudity, which they’d heard about but never seen. They never screened it. They refused to show it. The first time ever that an invited film was never screened.

And then we left and took it to Paris and showed it at the Cinematheque, and then took it to London, all in our suitcases. And we met Robert and we must have shown it in Robert’s apartment. He was renting his apartment from Kenneth Tynan and I was very impressed by that. It was pretty empty, that apartment – we went over there a number of times. Robert would just call up Paul McCartney or John Lennon. A lot of people came. Paul McCartney lent us one of the projectors.

Paul Morrissey – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

Robert called and asked me to bring Paul’s 16mm sound projector, because Chelsea Girls needed two projectors used simultaneously. So I took it over, arrived at 23 Mount Street and found about fifty or more people crammed in, lying all over the floor, all the Warhol entourage. We showed the movie and someone complained about the noise and the police came. Robert had this amazingly arrogant attitude towards the police which stopped them coming in. They tried. They were pointing to people passed out on the floor, saying, ‘Is he all right?’, but Robert just ignored this and ordered or pushed them back out on to the landing. ‘

Stash Klossowski – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

Dear Robert,

What a drag… you know what I mean.

Brother Nick rang and asked about the bread. All will be well, I’ll be back in London on Sunday, and on Monday I’ll sort it out.

Everybody was amazed by the whole scene, as you’ve guessed, and rally is the word.

Thursday was one of those days… bank raid shooting, Jayne Mansfield dead… etc… and I tore a ligament in sympathy, so I am hobbling round the Wirral. Jane sends her love, love, and is baking a file cake. I send mine. The handcuff pictures in the papers are incredible, and ‘aroused public sympathy’. Mind you, a tennis player from the Upton Tennis Club (where balls are known as spheres) was overheard saying that he would have given the blighters ten years if he’d been the judge… What???…

See you soon… nothing to say really.

Sincerely best wishes

Paul McCartney

Jane Asher

Sent June / July 1967 – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

In 1967, Robert Fraser pleaded guilty to charges of possession of heroin, and was sentenced to six months’ hard labour.

The thing I remember is his smell, after coming out of jail. He smelled like he’d been in jail. Scrubbed with carbolic soap or something — his clothes smelled. It put me off going to jail in a big way, that you’d smell jail. It was only for a couple of days.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

Linda bought me a Magritte for my birthday and it would be Robert she’d go to. She liked Robert a lot. He was one of our friends. Funnily enough, our kids didn’t, because he was too arrogant. And he was often drunk, and they were little and they couldn’t understand it. And he would say to them, ‘Make the fire, will you?’ And they would go behind his back and make little fuck-off signs. They weren’t intimidated by this slightly overbearing bloke. They liked him when he got on the wagon. He’d come down to our house in Sussex and then he was a changed person and they could handle him very easily then. But it was when he was being himself and a little indulgent — my kids didn’t enjoy that. They didn’t like Ringo either. Although he’s a bit of a darling. But he had the same problem – he had a major alcoholic problem.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

I remember seeing Robert outside Cicconis, this posh Italian restaurant, and he was then hanging out with James Mayor, who’d become a logical successor in a way. That was the last time I saw him. He seemed OK, a little quieter than usual. I remember Linda kissing him and noticing marks on his face. It was AIDS. I thought it was quite brave of her to kiss him. That was the first year anyone had heard about AIDS and nobody really knew how to deal with it. So my final memory of him is him walking away from Cicconis towards Cork Street. I waved and he turned round. I said, ‘Bye. See you, Robert.’ He turned away, didn’t look back and turned the corner. And I got a horrible feeling. I said, “That might be the last time I see him.’ And in fact it was.

Paul McCartney – From “Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser” by Harriet Vyner, 1999

He was very clean, very sober, but I think he started to think, maybe I’m clean, maybe I’m sober, but I’m boring now. We would still buy the odd Magritte through him and he was very good to run things by, he always had a good opinion. Our kids didn’t like him. He would come down to our house and he’d say, ‘Put a log on the fire, will you?’ and our kids would gesture behind his back as if to say, ‘Who does he think we are?’ But Robert just expected kids to do that. My kids don’t do that, they’re modem children – ‘Get it yourself, mush.’ They didn’t like him. The last time I saw him was outside Cecconi’s, a posh Italian restaurant opposite the Burlington Arcade which has very good food. It’s a bit of a watering hole. We’d had lunch with Robert and we were leaving. We were standing outside and he looked like he had little things on his skin, not pimples but dark marks on his face. I remember Linda touching and saying, ‘What’s that?’ ‘Oh! Thank God someone’s finally mentioned it, it’s uh, Kaposi’s sarcoma…’ I remember Linda kissing him, and this was the very early days of the AIDS epidemic and you didn’t know whether you ought to. But Linda kissed him and we said, ‘Okay, see you around.’ He walked from Cecconi’s down Burlington Gardens to Cork Street, and we just went, ‘Bye!’ I knew he wouldn’t turn round to wave, and I got a feeling that might be the last time I’d see him. A strange, eerie feeling. So the last thing I remember is just his dark suit, rear view, turning the corner, right, into Cork Street.

Paul McCartney – From “Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

There was a question of whether he wanted us to visit him. He was staying with his mother at that time, and I don’t know whether she acknowledged the fact that he had AIDS or whether it would be appropriate, but we’d get reports from our friend Brian Clarke. I remember sending him a photograph of a piece of pottery I’d done which was like a flat Duke of Edinburgh: Giacometti visits the Duke of Edinburgh. Linda had taken a photograph of it so we sent him some photos. And for the first time in my life I said, ‘Cheers, Bob’. I’d never called him Bob. He wrote back: ‘Bob? Bob? Who are you talking to?’ Actually there was a joke going around then that he was going to open a gallery called Bob’s Art Shop, so that’s where it came from. He eventually died at his mum’s place. The lovely thing was that he eventually went home to mummy; which for a public-school boy was nice because he’d been separated from mummy aged six to go to prep school, then he went on to Eton. I thought that was good for him and Brian said, “He’s quite enjoying it, actually. He’s enjoying being spoiled.’ His mum was pampering him. And so he went from the cradle to the grave, as it were. And then suddenly he was just gone.

Paul McCartney – From “Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

Jan 23, 1969

Jan 25, 1969 • Songs recorded during this session appear on Let It Be (Limited Edition)

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.