Release date Jul 17, 1968

Yellow Submarine (Animated film)

Animated film • For The Beatles • Directed by George Dunning

Last updated on September 7, 2024

Release date Jul 17, 1968

Animated film • For The Beatles • Directed by George Dunning

Last updated on September 7, 2024

From Wikipedia:

Yellow Submarine (also known as The Beatles: Yellow Submarine) is a 1968 animated musical adventure film inspired by the music of the Beatles, directed by animation producer George Dunning, and produced by United Artists and King Features Syndicate. Initial press reports stated that the Beatles themselves would provide their own character voices. However, aside from composing and performing the songs, the real Beatles participated only in the closing scene of the film, while their cartoon counterparts were voiced by other actors.

The film received widespread acclaim from critics and audiences alike, in contrast to the Beatles’ previous film venture Magical Mystery Tour. Pixar co-founder and former chief creative officer John Lasseter has credited the film with bringing more interest in animation as a serious art form, which was thought of as a children’s medium at the time. Time commented that it “turned into a smash hit, delighting adolescents and aesthetes alike.” Half a century after its release, it is still regarded as a landmark of animation.

John Lennon later said: “I think it’s a great movie, it’s my favourite Beatle movie. Sean loves it now, all the little children love it.”

Plot

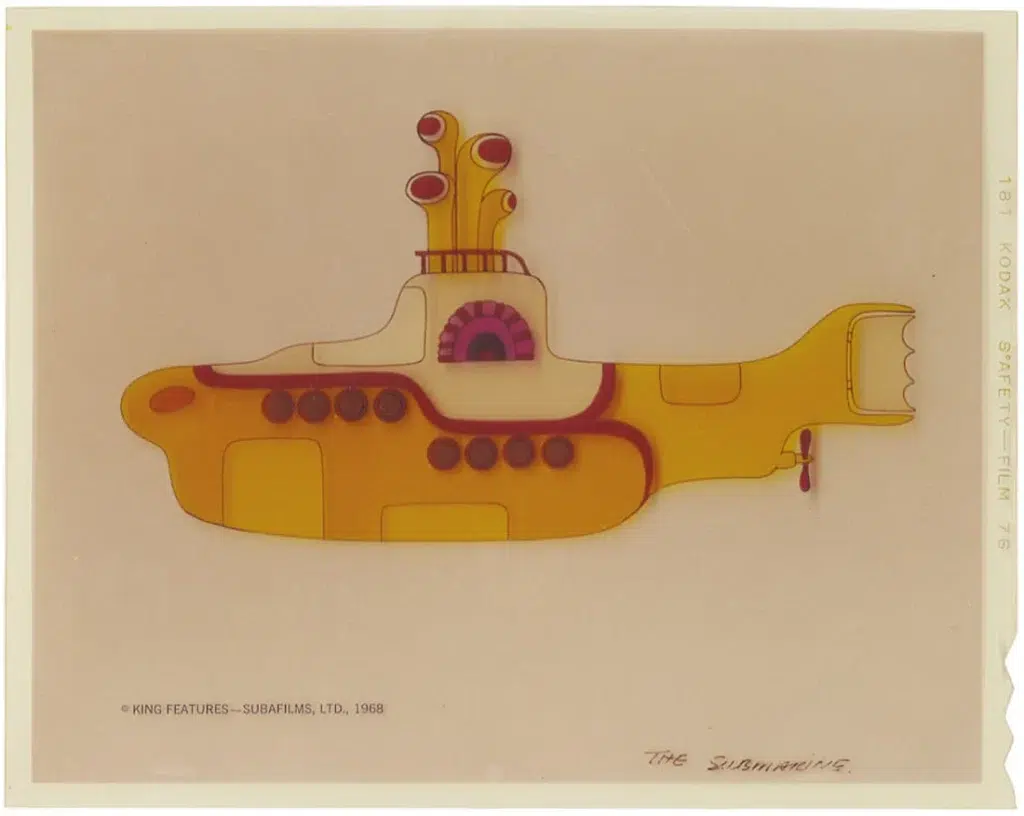

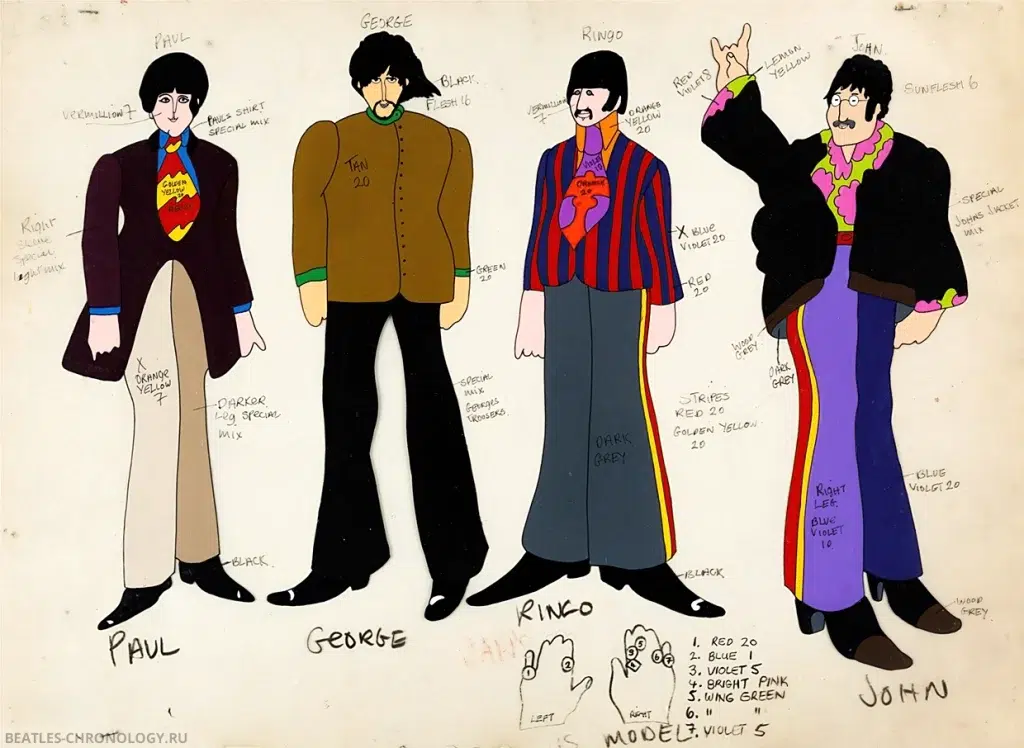

Pepperland is a cheerful, music-loving paradise under the sea, home to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The titular Yellow Submarine rests on an Aztec-like pyramid on a hill. At the edge of the land is a range of high blue mountains.

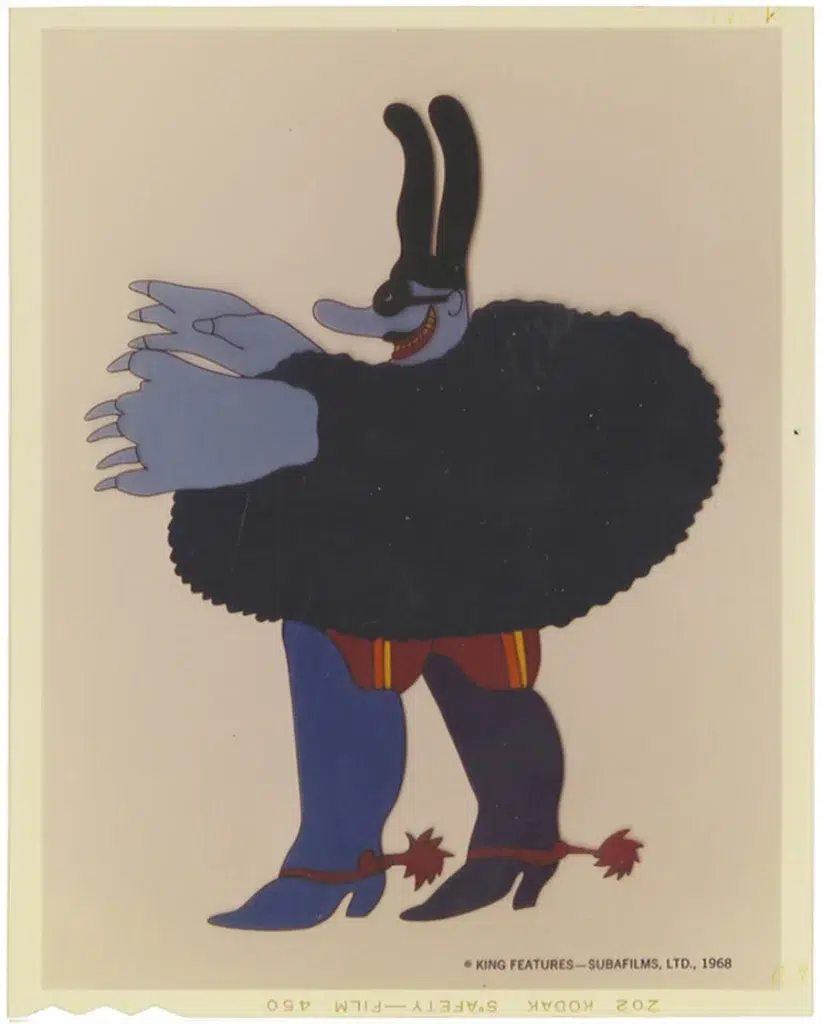

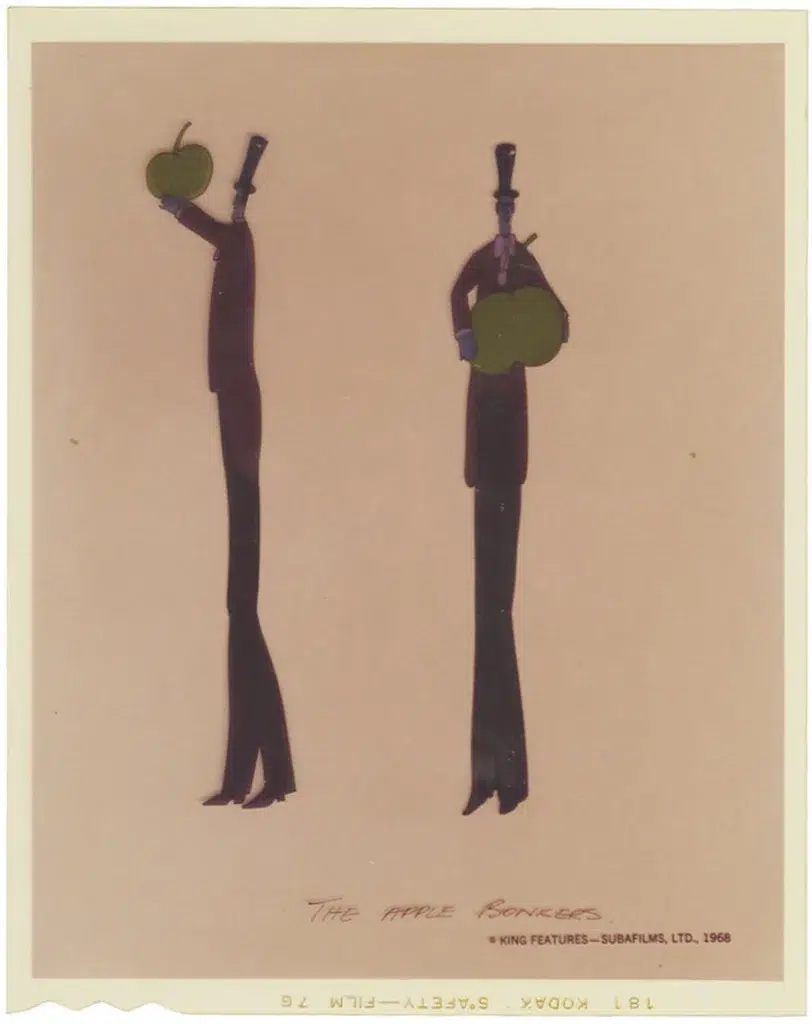

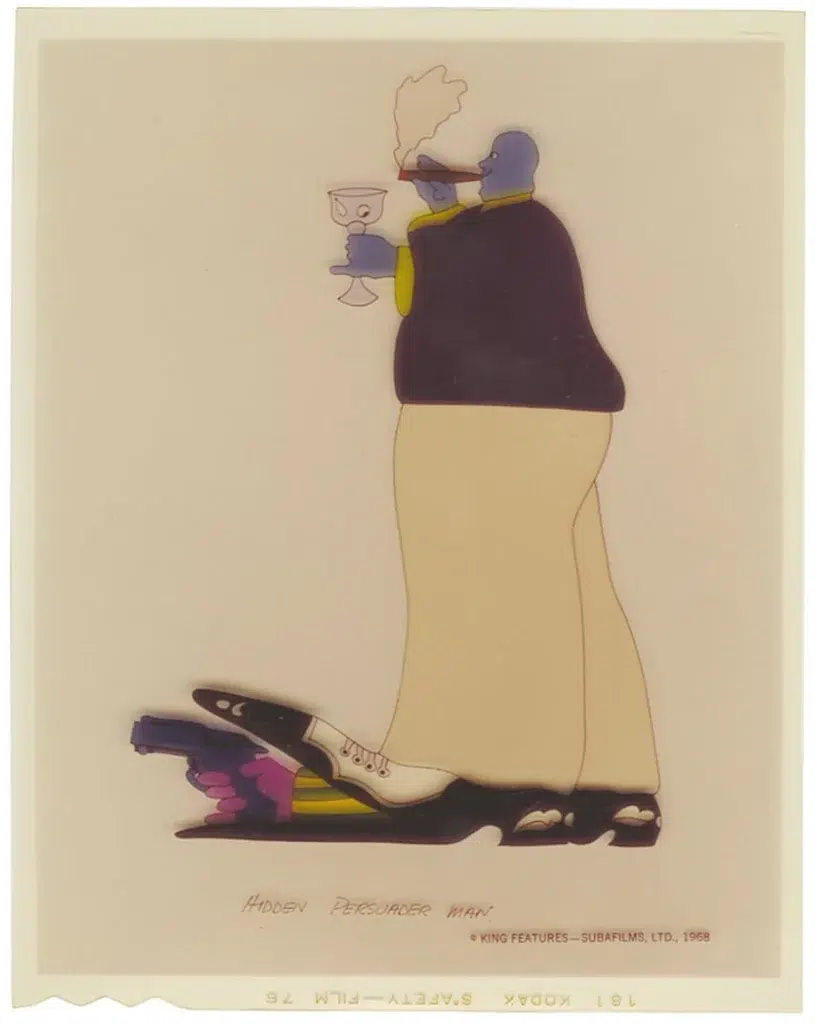

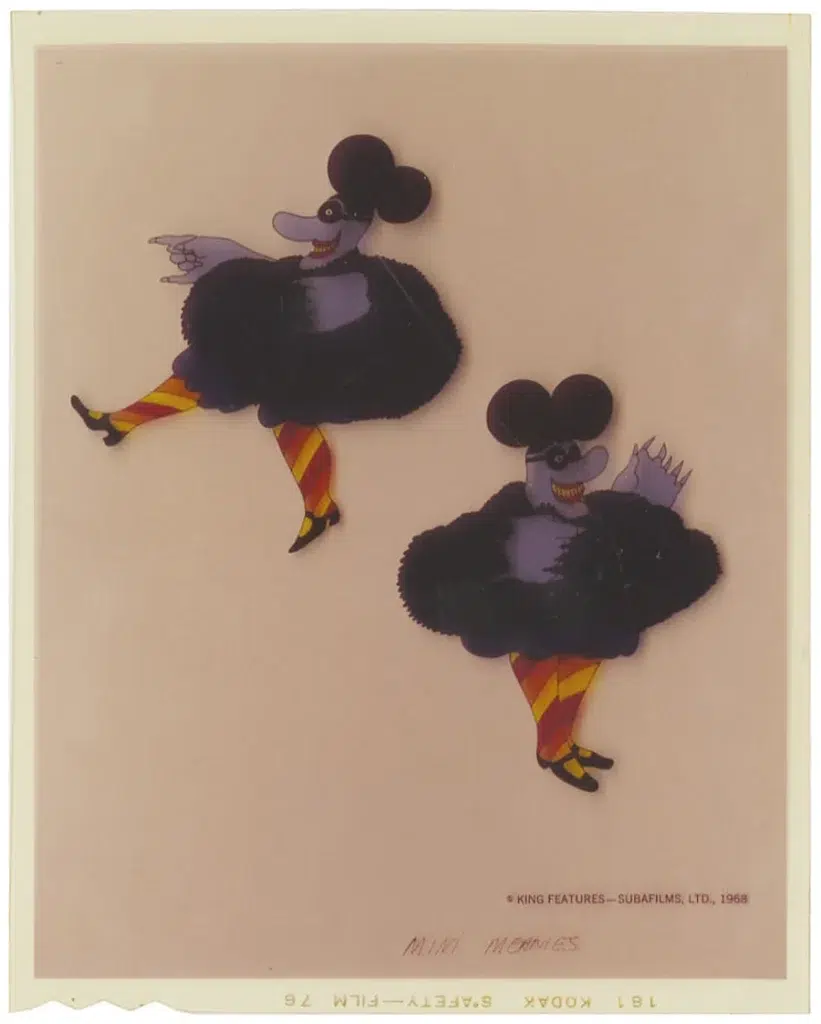

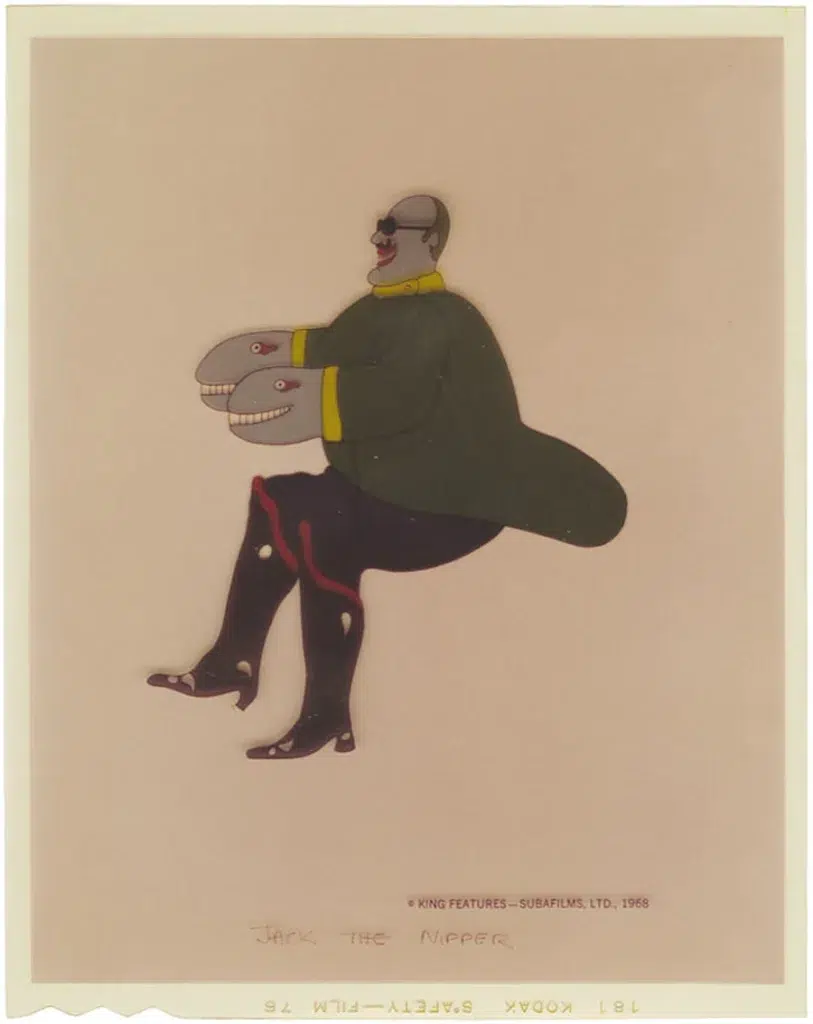

The land falls under a surprise attack from the music-hating Blue Meanies, who live beyond the mountains. The attack starts with a music-proof glass globe that imprisons the band. The Blue Meanies fire projectiles and drop apples (a reference to the Beatles’ then-new company Apple Corps) that render Pepperland’s residents immobile as statues, and drain the entire countryside of colour.

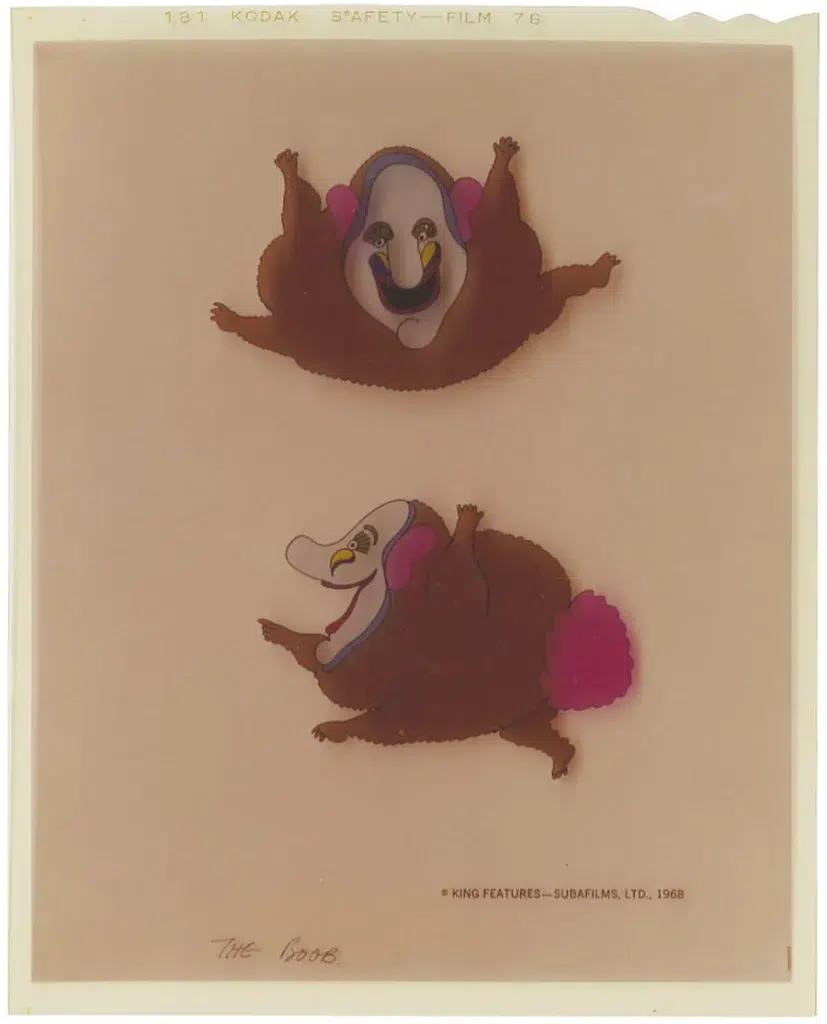

In the last minutes before his capture, Pepperland’s elderly Lord Mayor sends Young Fred to get help. Fred takes off in the Yellow Submarine (“Yellow Submarine“). He travels to Liverpool (“Eleanor Rigby“), where he follows a depressed Ringo to “The Pier”, a house-like building on the top of a hill, and persuades him to return to Pepperland with him. Ringo collects his mates John, George, and Paul. The four decide to help Old Fred, as they call him, and journey with him back to Pepperland in the submarine. As they operate the submarine, they sing “All Together Now“, after which they pass through several regions on their way to Pepperland, including the Sea of Time, where time flows both forwards and backwards (“When I’m Sixty-Four“), the Sea of Science (“Only a Northern Song“) and the Sea of Monsters, where Ringo is rescued from monsters after being ejected from the submarine. In the Sea of Nothing, the protagonists meet Jeremy Hillary Boob Ph.D., a short and studious creature (“Nowhere Man“). As they prepare to leave, Ringo feels sorry for the lonely Boob, and invites him to join them aboard the submarine. They arrive at the Foothills of the Headlands, where they are separated from the submarine and Old Fred (“Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds“). They then find themselves in the Sea of Holes, an expanse of flat surfaces with many holes. Jeremy is kidnapped by a Blue Meanie, and the group finds their way to Pepperland.

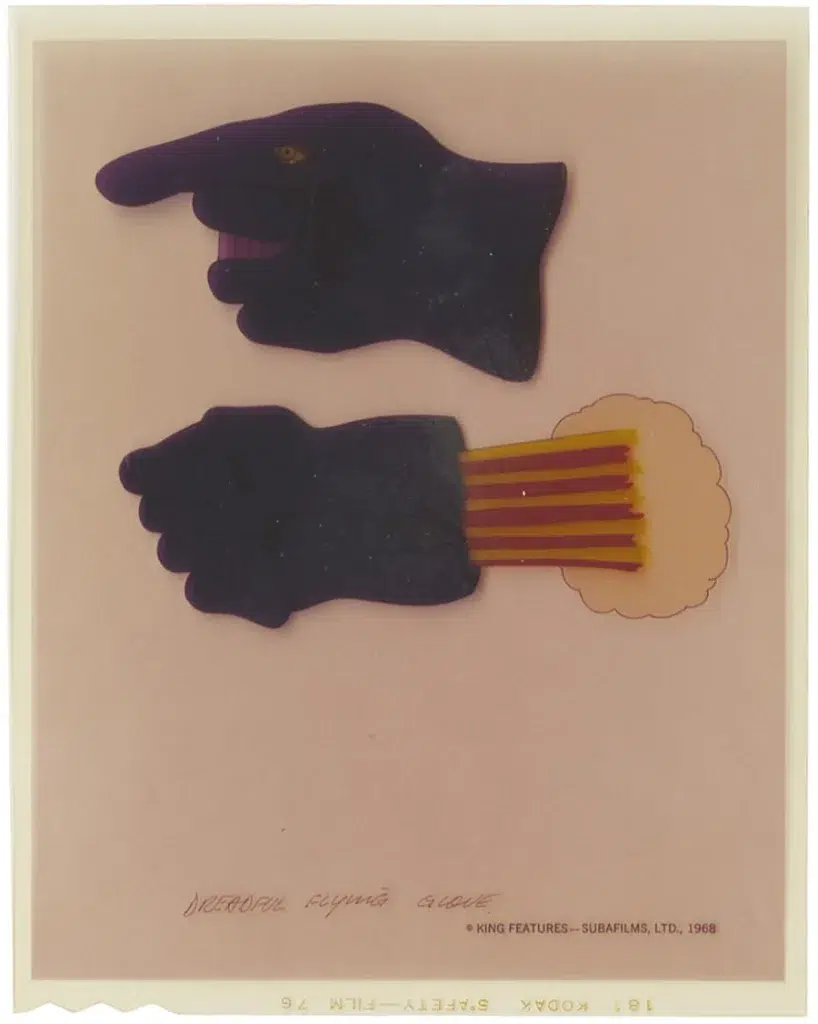

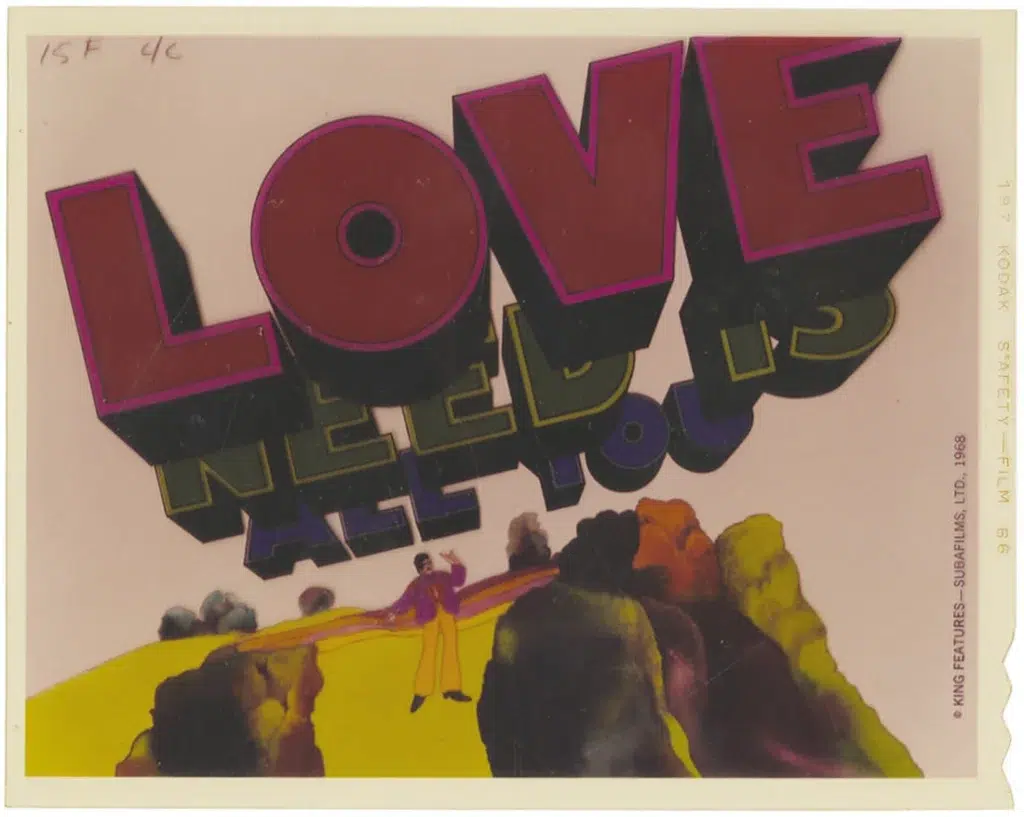

Reuniting with Old Fred and reviving the Lord Mayor, they look upon the now-miserable, grey landscape. The Beatles dress up as Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and steal some instruments. The four rally the land to rebellion (“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band“). The Chief Blue Meanie retaliates by sending out the Dreadful Flying Glove, which John defeats by singing “All You Need is Love.” Pepperland is restored to colour as its flowers re-bloom and its residents revive. The original Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band are released, and join the Beatles in combating the Meanies’ multi-headed dog (“Hey Bulldog“). Jeremy performs some “transformation magic” on the Chief Blue Meanie, causing the Meanie to bloom roses and sadly concede defeat. John extends an offer of friendship, and the Chief Blue Meanie has a change of heart and accepts. An enormous party ensues (“It’s All Too Much“).

The real Beatles then appear in live-action, and playfully show off souvenirs from the events of the film. George has the submarine’s motor, Paul has “a little ‘love’,” and Ringo has “half a hole” in his pocket (having supposedly given the other half to Jeremy). Ringo points out John looking through a telescope, which prompts Paul to ask what he sees. John replies that “newer and bluer Meanies have been sighted within the vicinity of this theatre” and claims “there is only one way to go out… Singing!” The four oblige with a short reprise of “All Together Now”, which ends with translations of the song’s title in various languages appearing in sequence on the screen. […]

Development

The Beatles were not enthusiastic about participating in a new motion picture, having been dissatisfied with their second feature film, Help! (1965), directed by Richard Lester. However, they saw an animated film as a favourable way to complete their commitment to United Artists for a third film. Many fans have assumed that the cartoon did not satisfy the contract, but Let It Be (1970) was the film not connected to the original three-picture deal.

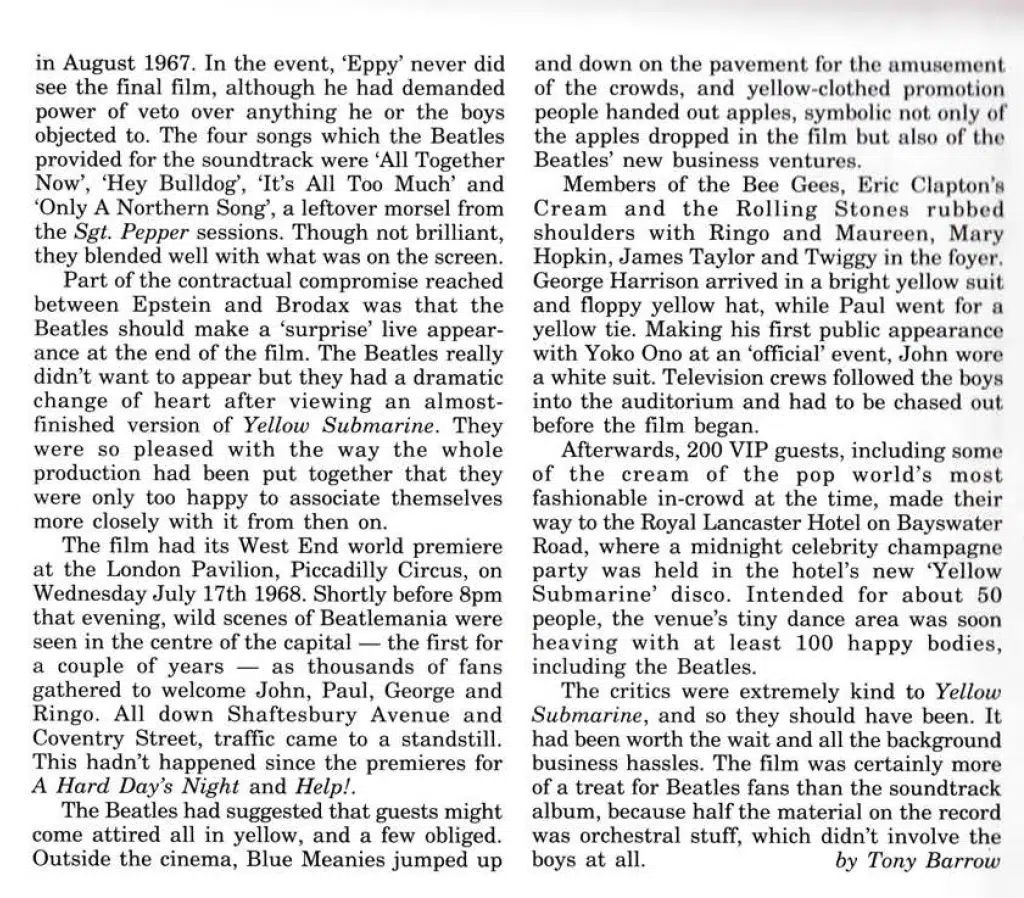

The Beatles make a live-action cameo appearance in the final scene, which was filmed on 25 January 1968, shortly before the band’s trip to India. This was done primarily to fulfill their contractual obligation to United Artists to actually appear in the film. The cameo was originally intended to feature a post-production psychedelic background and effects, but because of time and budget constraints, a blank, black background remained in the final film. While Starr and McCartney still looked the same as their animated counterparts, Lennon’s and Harrison’s physical appearances had changed by the time the cameo was shot. Both were clean-shaven, and Lennon had begun to grow his hair longer with accompanying mutton-chop sideburns.

The original story was written by Lee Minoff, based on the song by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, and the screenplay was penned by four collaborators including Erich Segal. George Harrison’s character’s recurring line “It’s all in the mind” is taken from The Goon Show.

As with many motion-picture musicals, the music takes precedence over the actual plot, and most of the story is a series of set pieces designed to present Beatles music set to various images, in a form reminiscent of Walt Disney’s Fantasia (and foreshadowing the rise of music videos and MTV thirteen years later).[citation needed] Nonetheless, the film still presents a modern-day fairy tale representing the values of its intended hippie audience.

The dialogue is littered with puns, double entendres and Beatles in-jokes. In the DVD commentary track, production supervisor John Coates states that many of these lines were written by Liverpudlian poet Roger McGough, though he received no credit in the film.

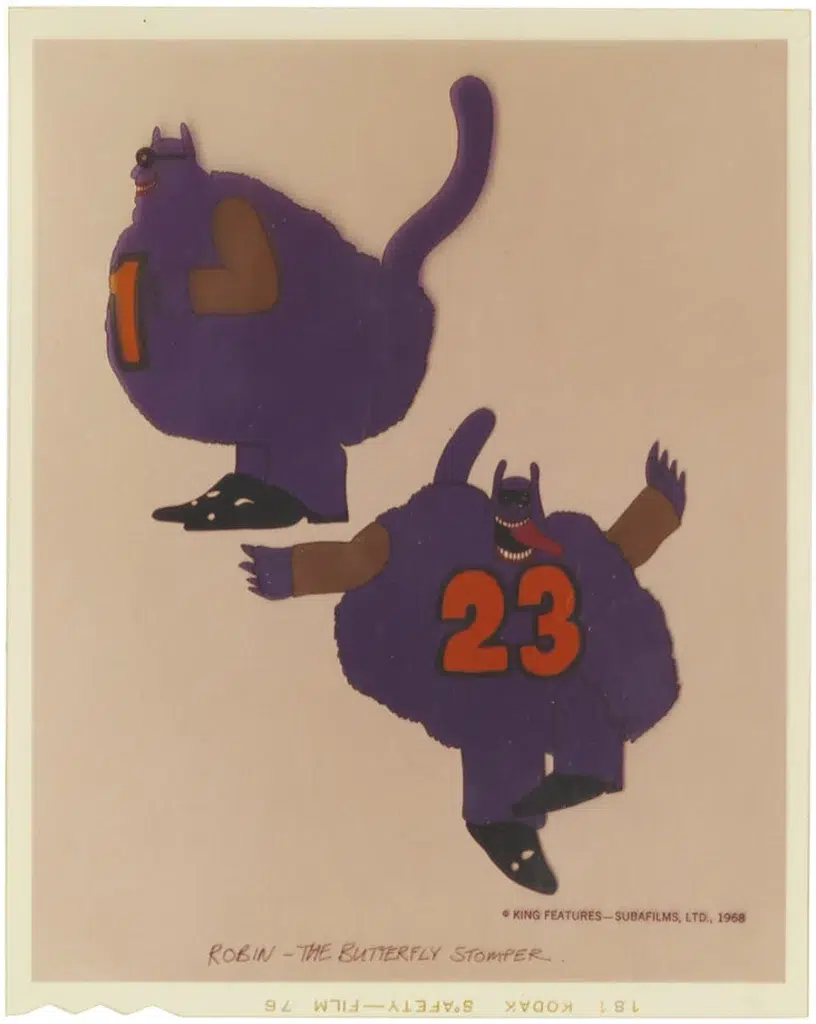

In the DVD commentary track, Coates states that the Meanies were always intended to be coloured blue. However, Millicent McMillan recalls that the Blue Meanies were originally supposed to be red, or even purple, but when Heinz Edelmann’s assistant accidentally changed the colours, the film’s characters took on a different meaning. Coates acknowledges in the commentary that the “are you Bluish? You don’t look Bluish” joke in the film is a pun on the then-contemporary expression “you don’t look Jewish”, but that it was not intended to be derogatory.

Animation

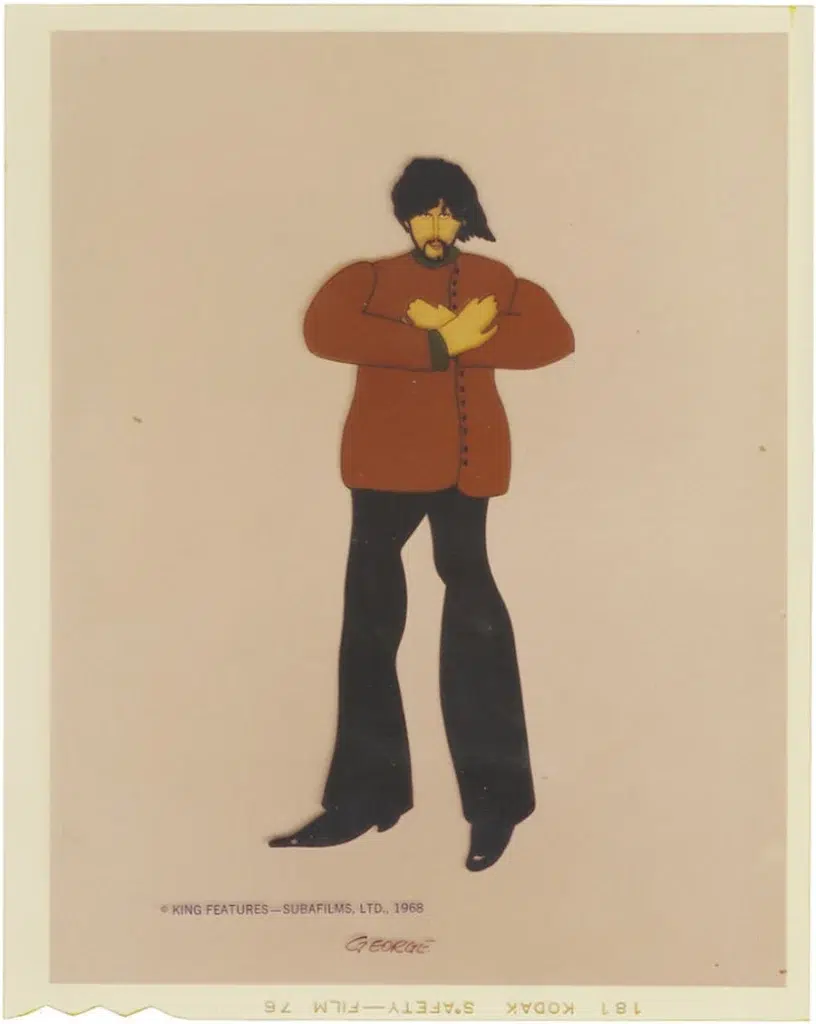

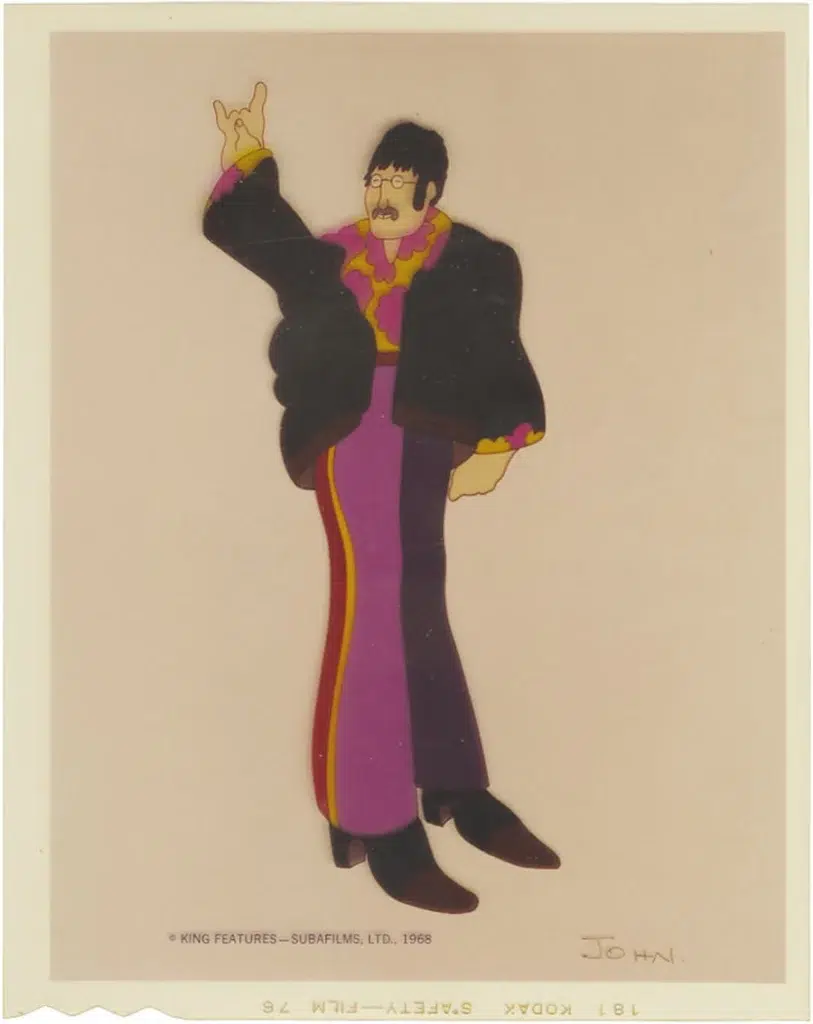

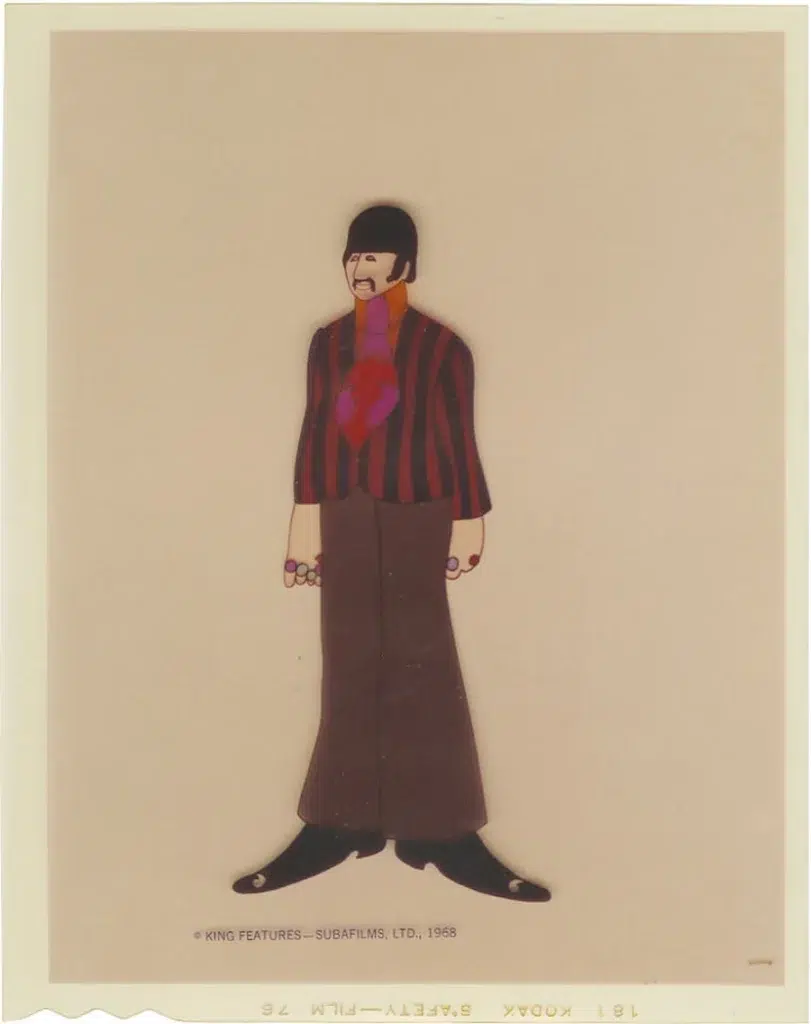

The Beatles’ animated personas were based on their appearance during the Sgt Pepper’s press party at Brian Epstein’s house, on May 19, 1967. The film also includes several references to songs not included in the soundtrack, including “A Day in the Life,” the lyrics of which are referenced in the “Sea of Holes” scene, the orchestral breaks earlier in the film are also taken from the song.

National and foreign animators were assembled by TVC. American animators Robert Balser and Jack Stokes were hired as the film’s animation directors. Charlie Jenkins, one of the film’s key creative directors, was responsible for the entire “Eleanor Rigby” sequence, as well as the submarine travel from Liverpool, through London, to splashdown. Jenkins also was responsible for “Only a Northern Song” in the Sea of Science, plus much of the multi-image sequences. A large crew of skilled animators, including (in alphabetical order) Alan Ball, Ron Campbell, John Challis, Hester Coblentz, Geoff Collins, Rich Cox, Duane Crowther, Tony Cuthbert, Malcolm Draper, Paul Driessen, Cam Ford, Norm Drew, Tom Halley, Dick Horne, Arthur Humberstone, Dennis Hunt, Greg Irons, Dianne Jackson, Anne Jolliffe, Dave Livesey, Reg Lodge, Geoff Loynes, Lawrence Moorcroft, Ted Percival, Mike Pocock, Gerald Potterton, and Peter Tupy, were responsible for bringing the animated Beatles to life. The background work was executed by artists under the direction of Alison de Vere and Millicent McMillan, who were both background supervisors. Ted Lewis and Chris Miles were responsible for animation cleanup.

George Dunning, who also worked on the Beatles cartoon series, was the overall director for the film, supervising over 200 artists for 11 months. “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” was Dunning’s idea, which he turned over to Bill Sewell, who delivered more than thirty minutes of rotoscoped images. By that time, Dunning was unavailable, and Bob Balser, with the help of Arne Gustafson, edited the material to its sequence length in the film.

The animation design of Yellow Submarine has sometimes been incorrectly attributed to famous psychedelic pop art artist of the era Peter Max, but the film’s art director was Heinz Edelmann. Edelmann, along with his contemporary Milton Glaser, pioneered the psychedelic style for which Max would later become famous, but according to Edelmann and producer Al Brodax, as quoted in the book Inside the Yellow Submarine by Hieronimus and Cortner, Max had nothing to do with the production of Yellow Submarine.

Edelmann’s surreal visual style contrasts greatly with the efforts of Walt Disney Animation Studios and other animated Hollywood films that had been previously released at the time (a fact noted by Pauline Kael in her positive review of the film ). The film uses a style of limited animation. It also paved the way for Terry Gilliam’s animations for Do Not Adjust Your Set and Monty Python’s Flying Circus (particularly the Eleanor Rigby sequence), as well as the Schoolhouse Rock vignettes for ABC and similar-looking animation in early seasons of Sesame Street and The Electric Company. (Only one of the animation staff of Yellow Submarine, Ron Campbell, contributed subsequent animation to Children’s Television Workshop).

Music

In addition to the 1966 title song “Yellow Submarine,” several complete or excerpted songs, four previously unreleased, were used in the film. The songs included “All Together Now,” “Eleanor Rigby“, “It’s All Too Much” (written by Harrison), “Baby, You’re a Rich Man” (which had first appeared as the B-side to “All You Need Is Love” in June 1967), “Only a Northern Song” (a Harrison composition originally recorded during sessions for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band), and “Hey Bulldog.” Written by Lennon, this last track was cut from the film before it opened in the US. “Hey Bulldog” was restored for the US theatrical and home video reissue in 1999. The four new songs used on the soundtrack album were not considered of high enough quality for appearance on a “regular” Beatles album.[citation needed]

The film’s instrumental music was an orchestral score composed and arranged by George Martin. One of the film’s cues, heard after the main title credits, was originally recorded during sessions for “Good Night” (a track on The Beatles, also known as the “White Album”) and would have been used as the introduction to Ringo Starr’s White Album composition “Don’t Pass Me By.” The same cue was later released as “A Beginning” on the 1996 Beatles compilation Anthology 3. […]

Reception

Yellow Submarine received widespread critical acclaim. Released in the midst of the psychedelic pop culture of the 1960s, the film drew in moviegoers both for its lush, wildly creative images and its soundtrack of Beatles songs. The film was distributed worldwide by United Artists in two versions. The version shown in Europe included an extra musical number, “Hey Bulldog,” heard in the final third of the film. For release in the United States, the number was replaced with alternative animation because of time constraints. It was felt that, at the time, American audiences would grow tired from the length of the film.

The film realized receipts of more than $992,000 USD in the US and more than $280,000 USD internationally. For reference, the top-grossing films for 1968 were in excess of $50M in the domestic market alone.On Rotten Tomatoes, the film currently holds a 95% approval rating based on 60 reviews, with an average rating of 7.91/10. The website’s critical consensus states: “A joyful, phantasmagoric blend of colorful animation and the music of the Beatles, Yellow Submarine is delightful (and occasionally melancholy) family fare.” On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 78 out of 100, based on 17 critics, indicating “generally favourable reviews.”

Rights and distribution

Of all the Beatles films released by United Artists, Yellow Submarine had been the only one to which UA retained the rights, leading up to its purchase by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1981. In 2005, Sony Pictures Entertainment led a consortium that purchased MGM and UA. SPE handled theatrical distribution for MGM until 2012. 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment was responsible for home video distribution when the most recent home video release went out of print until 30 June 2020.

For the 50th anniversary of the movie in 2018, it was screened in the UK and Ireland for one day on 8 July 2018, and in the US from 8 July 2018. Amazon negotiated exclusive streaming rights to the film via its Prime Video service, starting 13 July 2018 in the UK, the US, Canada, Germany, Spain, France and Italy under a deal with Apple Corps. The companies declined to disclose the length of Amazon’s exclusive rights.

Home media

With the dawn of the home-video era came an opportunity to release Yellow Submarine on VHS and LaserDisc. However, it was held up by United Artists for some years over music-rights issues. Coinciding with the CD release of the soundtrack album, United Artists issued the film on home video on 28 August 1987. To the disappointment of fans in the UK, the film was presented in its US theatrical version, thereby omitting the “Hey Bulldog” scene. The video was discontinued around 1990, and for many years copies of the original VHS issue were considered collectables.

On 14 September 1999, then-rights holders Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Apple reissued the film for the first time on DVD and VHS using restoration techniques of the time. The sound was remixed to Dolby 5.1, and the film was re-edited to its European theatrical version, with the “Hey Bulldog” number restored. This version (released through MGM Home Entertainment) went out of print once the rights reverted to Apple Corps.

Restoration

On 20 March 2012, Apple Corps announced that the film had been restored by hand for DVD and Blu-ray release on 28 May 2012 (29 May in North America), later delayed one week to 4 June 2012 (5 June in North America). The company stated: “The film’s soundtrack album will be reissued on CD on the same date. The film has been restored in 4K digital resolution for the first time – all done by hand, frame by frame.” The delicate restoration was supervised by Paul Rutan Jr and his team, which included Chris Dusendschon, Rayan Raghuram and Randy Walker. No automated software was used to clean up the film’s repaired and digitised photo-chemical elements. The work was done by hand, a single frame at a time, by 40 to 60 trained digital artists, over several months.

In addition to the DVD and Blu-ray re-release, the restored version also received a limited theatrical run in May 2012.

For the 50th anniversary of the film, the soundtrack and score were remixed in 5.1 stereo surround sound at Abbey Road Studios by mix engineer Peter Cobbin.

Soundtrack

On 14 September 1999, United Artists and Apple Records digitally remixed the audio of the film for a highly successful theatrical and home video re-release. Though the visuals were not digitally restored, a new transfer was done after cleaning the original film negative and rejuvenating the colour. A soundtrack album for this version was also released, which featured the first extensive digital stereo remixes of Beatles material.

The previous DVD release also featured a music-only audio track, without spoken dialogue, leaving only the music and the songs. […]

Scrapped remake

In August 2009, Variety reported that Walt Disney Pictures and filmmaker Robert Zemeckis were negotiating to produce a 3D computer-animated remake of the film. Motion capture was to be used, as with Zemeckis’ previous animated films The Polar Express (2004), Monster House (2006), Beowulf (2007) and A Christmas Carol (2009). Variety also indicated that Disney hoped to release the film in time for the 2012 Summer Olympics in London. Disney and Apple Corps officially announced the remake at the inaugural D23 Expo on 11 September 2009.

Comedian Peter Serafinowicz was cast to voice Paul, Dean Lennox Kelly as John, Cary Elwes as George, Adam Campbell as Ringo and David Tennant as the Chief Blue Meanie. California-based Beatles tribute band The Fab Four was cast to perform the performance capture animation for the animated Beatles.

In May 2010, Disney closed Zemeckis’ digital film studio ImageMovers Digital after unsatisfactory box-office performance of A Christmas Carol. On 14 March 2011, Disney abandoned the project, citing the disastrous opening weekend results of Simon Wells’ Mars Needs Moms. Criticism toward motion-capture technology was also a factor.

After its cancellation at Disney, Zemeckis tried to pitch the remake to other studios. By December 2012, Zemeckis expressed that he had lost interest in the project, stating: “That would have been great to bring the Beatles back to life. But it’s probably better not to be remade – you’re always behind the 8-ball when do you [sic] a remake.”

In 2021, footage of the remake surfaced online, revealing that the film would have potentially utilized soundbites from the original and even recreate certain scenes. One of the more notable differences was a sequence during Ringo’s introduction where he was going to be tempted by a siren presumably created by the Blue Meanies.

The [Beatles Cartoon] series ran for three years. During that time Brian made a deal with United Artists to make three pictures. He did A Hard Day’s Night and Help! But the third picture came up and the boys didn’t want to do it. They wanted to go to India. So I contacted UA and I suggested that I could do an animation and they could go to India and everybody would be happy. Brian consented and the deal got a little better for us. Lots of treatments were submitted by important people like Joe Heller, who wrote Catch 22. Brian was impossible. He dismissed Heller’s treatment because the cover was purple and Brian didn’t like purple. It got up to about a dozen treatments. I wrote one. Erich Segal wrote one. He’s a wonderful guy. He’s also full of himself.

Al Brodax – Producer – From MOJO, October 1999

I was an assistant professor of classics at Yale. I was asked by the late Richard Rodgers to collaborate with him on a musical. On the day Richard Rodgers made the announcement, Al Brodax flew to London and read the New York Times on the way. He saw the article about me and when he got to London and I found chaos he said, We’ve got to get this guy, he just might be the ticket.

Erich Segal – From MOJO, October 1999

The Beatles thought I was too old. They wanted someone younger and I called a man who said his kid brother might fit the bill because he’s got long hair and wears crazy suits. That was Lee Minoff. Lee could not write dialogue but he did come up with names that I thought were intriguing like The Monstrous Blues and The Snapping Turtle Turks and Old Fred. The Beatles liked Lee but they hated the treatment. So we cobbled something else together, using that treatment as the basis and just called it Yellow Submarine.

Al Brodax – From MOJO, October 1999

Al Brodax talked to us about the possibility of doing a feature and we met at my house in London. Erich Segal came along as well. I talked to them about Yellow Submarine which they wanted to build the film around. I told them that I had very definite thoughts about this. There is a land of actual submarines – all different coloured and in fact it’s a commune. All four of us hoped for something a little bit groovier. Sort of more classic Pinocchio or Snow White. Right away, they made it clear they weren’t keen to do just a straight Disney thing.

Paul McCartney – From MOJO, October 1999

We consciously went away from the Disney style. We had a big sign up at the studio: Disney – The Opposite.

Al Brodax – From MOJO, October 1999

They said, “We think you’re further out now.” So from being rather childish, which that cartoon series most definitely was, they wanted to go completely psychedelic!

Paul McCartney – From MOJO, October 1999

I love cartoons – I love the Disney stuff. So, you know, the first thing when we heard people were going to do a cartoon I just thought, ‘Yeah, this could be the greatest Disney cartoon ever’ – I mean, with our music. But they were going more Pepper direction, so we said, ‘Well why don’t you just take a lot of songs we’ve got already?‘

Paul McCartney – from Yellow Submarine | The Beatles

The film was made opposite where my office was in London. They had hired a floor there. We had held initial talks with the creative leads. There were the people from King Features who had started the whole thing by doing a cute Beatles TV series, then they wanted to do a feature. So I thought “Wow! Great – we could do a sort of Disneyesque fabulous feature magical and this and that”. But they – rightly I think – decided it had to reflect the spirit of the times. They wanted to make something more adventurous. They then formed a team of some classic animators and then some very innovative guys, and Heinz Edelmann was the leader of the innovative group. But they were just across the square from my office so I would just go in there and pay visits and see him sitting there at his desk. I remember seeing the Blue Meanies emerge. I’d give feedback. I remember him as being a cool cat, a zany guy.

Paul McCartney – From Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art”, February 2012

What were you initially hired to do exactly. what did they tell you they were hiring you for?

This is what they didn’t tell me. I went to London to discuss this and said, “Yes. what do you want from me? Do you want me to do the design?” I wasn’t interested in the cash. I wanted to pick up a few things about animation. I’d made some short films of my own (now all lost), and wanted to learn more. This was my main interest and I saw this as a short-term thing. So I asked them, “What do you want me to do? Do I do the characters?” “No, we’ve got our own people doing that.” “So do you want me to do the backgrounds then?” “No, no, we’ve got our own people doing those.” So I said, “Well then, what do you want me to do?” and they said, “Oh, you do the little odd things you do.”

What odd things were you doing?

I didn’t honestly know what the little odd things were supposed to be, but suddenly they asked me to do the Beatles characters. I did those in Dusseldorf and they liked them, apparently. Then I went back to London without a work permit expecting them to say they’d had enough. How many odd things can one do? I stayed three or four weeks and in that time almost nothing at all was happening because they couldn’t agree to a script. They only knew the film was to be called Yellow Submarine.

Heinz Edelmann – From Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art”, February 2012

The boys didn’t think it was a good idea at all! The idea of being portrayed in cartoon form was basically abhorrence to them, particularly when the guy who was doing it, the only track record they could think of to what he had done was The Flintstones!

George Martin – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

You know what Al Brodax used to do? Brodax got half the Yellow Submarine out of my mouth! You know the idea for the hoover? The machine that sucks people up? All those were my ideas! They used to come to the studio and, sort of, chat, ‘Hi, John, old bean. Got any ideas for the film?’ And I’d just spout out all this stuff, and they went off and did it, you know.

John Lennon – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

We had to do some songs that were exclusive to the film. I don’t think we were too keen because we were quite busy recording other things and we probably wanted a bit of time off.

Paul McCartney – From MOJO, October 1999

There was a commitment for The Beatles to do four songs for the film. Apparently, they would say this is a lousy song, let’s give it to Brodax.

Al Brodax – From MOJO, October 1999

Their reaction was, “OK, we’ve got to supply them with these bloody songs but we’re not going to fall over backwards. We’ll let them have them whenever we feel like it, and we’ll give them whatever we think is right.”

George Martin – From MOJO, October 1999

The Beatles are very, very enthusiastic about the new animated film Yellow Submarine. They have been calling us at all times with ideas. We have even had discussions at two o’clock in the morning! Their suggestions are very good. So far, all The Beatles ideas are being incorporated into the movie.

Al Brodax – American producer – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

The fact that they fixed a premiere 11 months ahead of starting without a script and without a storyboard was fairly crazy.

John Coates – Animation director – From MOJO, October 1999

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.