Thursday, June 20, 2024

Interview for Christies's

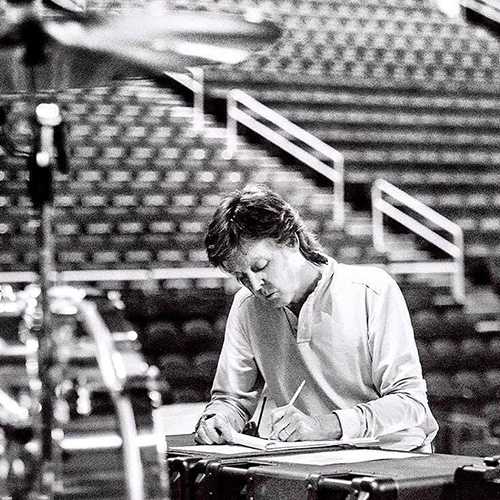

Here, there and everywhere: the never-before-seen photos Paul McCartney shot behind the scenes of Beatlemania

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Thursday, June 20, 2024

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Interview Jun 19, 2024 • Paul McCartney interview for paulmccartney.com

Article Jun 20, 2024 • Mexico tour dates announced

Interview Jun 20, 2024 • Paul McCartney interview for Christies's

Album Jun 20, 2024 • "Recording Vault Underdubbed Vol. 2" by Paul McCartney released globally

Article Jun 23, 2024 • Paul McCartney attends Taylor Swift's concert in Wembley

Next interview Mid-2024 • Interview for the 2024 "Got Back" tour book - Getting one on one with Paul ahead of hitting the road

The interview below has been reproduced from this page. This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

Darius Himes: This body of work is such a fabulous time capsule. How in the world did you rediscover these images, and what was it like to find them again?

Paul McCartney: I have an archivist, Sarah Brown, who works with me archiving the work of Linda [McCartney, Paul’s late wife]. One day, during a meeting about Linda’s photography, I happened to say to her, ‘Hey, I took some pictures in the Sixties. I wonder if we have them still.’

Sarah said, ‘Yes, you do,’ and she knew where they were. So we agreed to have another meeting and look at those photographs. She had relationships with a lot of galleries, including the National Portrait Gallery where my daughter Mary had done some work, and she said they’d like to look at them. So it went from me rediscovering these old pictures to the National Portrait Gallery looking at them, and they liked them. We started talking about what they’d like to do with them, and they eventually came up with the idea of an exhibition and a book.

DH: In her introduction to the book that accompanies the exhibition, Jill Lepore notes that the four of you received Pentax cameras as gifts in 1963. In several of your pictures we see John and Ringo wearing cameras around their necks. Were you the one who most regularly used your camera at that time? Why were you drawn to this medium?

PM: We were all very keen on photography, actually. The new modern reflex cameras had come out, and we each had one and liked to take pictures. Ringo recently had a book of his pictures [Photograph, 2015]. They’re pictures of an era. When you’re taking them you don’t ever think they’re going to be historical. You’re just taking a snapshot. But then this long after, you look back and say ‘Wow, this really captured the look, how we dressed, the hotel rooms, the style of the hotels.’ It brings the whole period back.

DH: It’s clear that photography has been an important part of your life from early on, and these early photos from Liverpool and London really illustrate that. What are your most striking memories of composing photographs during those days?

PM: I’ve always been interested in images, from the very first days when our family had a little box camera. I used to love the whole process of loading a roll of Kodak film into this Brownie camera.

When I was young, it was normally used for family portraits — nobody really thought much beyond that. When I went on holiday with my family to a holiday camp in Wales, I borrowed the camera for a day and took some photographs for memories of that trip, which I enjoyed a lot. I would pose and ask my brother to take a picture of me outside the hot dog store, because in England you didn’t really have hot dog stores. We used the camera to take pictures of each other. And from those very early days, I always enjoyed looking at good photography.

The kind of thing we would be exposed to would be Karsh of Ottawa, who was a big thing in England with his portraits of various luminaries in the newspapers. The Observer particularly had good sports photos. You’d see rugby players caked in mud scrambling around in a scrum, and they were artistic pictures. They weren’t just average newspaper pictures of the team lining up for a photo. It was much more cinema verité, and I was attracted to that.

Then, as time went on, I saw the work of other great photographers and really learnt to appreciate good photography. Culturally, things were popping, so you were starting to see the kind of things our parents had never seen because of all the new inventions like television and proper cameras. My interest in the visual arts continued right through, and when we went to Hamburg [in 1960], I met a woman called Astrid Kirchherr, who was a very good photographer. She’d invite us to her house where she’d take portraits. You’d just learn by seeing what she did, and she took some good early pictures of The Beatles.

DH: These photographs are from a seminal moment in The Beatles’ history: those amazing months at the end of ’63 and the beginning of 1964, when The Beatles toured Liverpool, London and Paris and then came to the United States for the first time. Did you sense that there was something momentous happening that you wanted to capture from your own perspective?

PM: Most of them I don’t remember taking, because it was a whirlwind. You know, it was great, that’s what we were aiming for. We’re kids from Liverpool. We wanted money, we wanted fame, we wanted to be great successes. So with that, came the fans. We were so excited just to be in America. It was great photographic material.

DH: Tell us how the self-portrait in the mirror came about. It’s a striking moment of self-awareness.

PM: It’s just a natural thing you know, if you’re trying to take a self-portrait. Beyond that, I just like things in mirrors. A lot of photographers do that. We were exposed suddenly to a lot of interesting photography. People like David Bailey, Norman Parkinson. They were really good, so you’d learned stuff off them. Bailey would use mirrors a lot. Seeing these really interesting photographs, it was natural to try and emulate them.

DH: Along with music, the 1960s witnessed a reimagining and invention of new pop art of all kinds. Photography was a huge area of innovation, as you note. How aware were you of creating new styles of photography?

PM: Well, we were looking at people who were taking photos in a new way. You’ve got to remember that what went before, French art stuff, cinema verité, it was all coming through. This was a few years after World War II. Now this was kind of a new world and a new future. So everyone was experimenting.

DH: You were aware of many of the movements in contemporary photography happening all around you. Your friend Jurgen Vollmer was working as an assistant to the great William Klein. You knew the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Do you think their work consciously affected you as you made images on those trips?

PM: When you’re young, you get excited by new and interesting things. I still do, but when you’re a teenager or in your 20s, you’re so driven and you soak up everything. It’s formative. But at that age, you don’t necessarily know how the things you enjoy fit into a wider narrative. With Elvis, for example, it took a while before we realised how important the influence of Sister Rosetta Tharpe or Jimmie Rodgers had been on him. You would just see Elvis and think, ‘Wow! I love this!’ And you would get excited and inspired by it. It’s the same with photography. We didn’t appreciate at the time how important photographers like Klein or Cartier-Bresson were to the story of the artform, we just thought their work was interesting.

Cartier-Bresson’s idea of the ‘decisive moment’ had probably been discussed with some of our friends at art college. We thought it was great our friend Jurgen from Hamburg had this cool job working for this interesting artist William Klein in Paris. We were excited for him, and he would tell us about it.

Growing up, I’d also taken a particular interest in the photography in The Observer newspaper. I was completely unaware of how important people like Jane Bown or Don McCullin were or how influential David Astor had been as an editor of the paper, but I found their photography exciting, a new way of looking at the world. Their photographs captured real life authentically.

All these conversations and thoughts would then feed into what we were doing. Some of it would be conscious, some unconscious. But when you engage with any piece of artwork — a photograph, a painting, a song — that can influence what you do. Even if you decide you don’t like an artwork, you still have an opinion on it, and that can be just as important as finding something you do like. We did this all the time with other people’s songs: What did we like about it? What would we have changed if it was our song? How could we write something better? If you’re creative, everything feeds into what you do, and so when you’re looking at my photographs from this time, you’re seeing me in dialogue with those guiding influences from my youth.

DH: Artists like Richard Avedon, Philip Jones Griffiths, Diane Arbus, David Bailey, and American street photographers Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, shifted our perception of how a photograph could function. How did working with some of these photographers, and seeing their work, change your own perception of what photography could do?

PM: Out of that list, I think we worked with Richard Avedon, Philip Jones Griffiths and David Bailey, and each had their own way of working and their own style. Garry Winogrand also caught some great snapshots of Beatlemania. Philip Jones Griffiths was backstage at our early shows. By then we had learned the best way to get the kind of reportage photographs he was taking was to just ignore the photographer and get on with what we needed to do. He captured the hustle and bustle of getting ready for a show and our life offstage.

I think what we learned from him was how those everyday moments, many of which were quite mundane, could be elevated into an interesting image. We realised that photographs don’t have to be of something big or eventful to be compelling. Linda was very good at capturing those kinds of images too. I’ve been fortunate to have lived many, many exciting experiences, but I still have very normal everyday experiences too. Getting the train home, driving the car somewhere, waiting for a friend to arrive. Linda was great at capturing those quiet, intimate and in some ways prosaic instances. So much of our lives is made up of those quieter moments. And if you capture that well, it can be quite breath-taking.

When we worked with Richard Avedon and David Bailey it would have been in a studio, and that’s a very different environment and vibe than having someone follow you around on tour. The feel and atmosphere of a photographer’s studio is created by the photographer themselves. We were coming into their world, and that has a big influence on how the photographs turn out.

The photos with Richard Avedon were a little more stylised than many of the things we’d done before. But he put us at our ease, and we felt comfortable with him so were willing to try interesting set ups that we hadn’t done before — like going topless! David Bailey was someone we used to see around the clubs and at parties so we knew him socially. A shoot with him was pretty social too, with lots of talking. He is interested in body language and how people hold themselves, so it could take a while to get the right setup.

This is something I mention in the book — when we started, we were working with photographers who didn’t necessarily specialise in photographing musicians because music photography wasn’t really a thing yet. We worked with quite old-fashioned portrait photographers because they were the only ones around. This all changed in the 60s, when a lot of younger photographers came onto the scene. Old rules were being broken and new ones being written, and we got to witness this first-hand. We were lucky enough to make friends and talk with many of these great photographers, so we learned a lot from hanging out and listening to their ideas. Then we would go try them out for ourselves.

DH: In the book, you write, ‘My camera was attracted to this new American universe of common people.’ So much of your music touches on the concerns and emotions of common people, and of course there is a long tradition within photography that is concerned with the ‘universe of common people.’ I’m reminded of Dorothea Lange, W. Eugene Smith, even Eugene Atget in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century. I’m curious who else you might have been looking at and inspired by?

PM: That’s my people. That’s where I’m from. I grew up in a working-class family in Liverpool. Those are the people I met. Those are the people I knew. I didn’t grow up detached from those people at all; I was right in the middle of them. My relatives would be those kind of working class people, the people I would know: the bus driver, the postman, the milkman. That was who I hung out with. That’s who I associated with.

When we came to America, that was one of the things we explained to Americans when they said, ‘Why do we need you in America?’ We said, ‘Well, we’re very like you. We have a lot in common.’ I have a lot in common with ordinary people.

DH: We’ve all been struck by the emotional vulnerability in some of these photographs from 1963–64. This was such a special and exhilarating moment in your collective lives. What was it like for you revisiting these images?

PM: Every picture brings back memories. I can try and place where we were and what we were doing to either side of the frame. Pictures of us with the photographers bring back memories of being in New York for the first time and being taken down to Central Park, the New York hard-bitten cameramen shouting out, ‘Hey Beatle, hey Beatle.’ We’d look at them and they’d take the picture. ‘One more for the West Coast.’ I remember all of those stories.

Then there’s the pictures out of the train windows, seeing American trains and railway yards. I like American trains to this day. I look at those things and think, Wow, I wonder how many people have hitched a ride on those in the old days. The other thing I do is, in the case of people I don’t know, I like to imagine their lives. So, the man who’s shovelling in the Pennsylvania train yard — I like to think about what he’s like when he goes home. What does he go home to? Does he say to people, ‘Hey, The Beatles went through on the train’? They fire my imagination, these photographs. I can think to the left, to the right, to the top, to the bottom of them. They bring back lots of stories, and that’s one of the reasons I love them.

DH: In several of the photographs, you focus in on a moment of calm amidst the ‘storm’ that was surrounding you — John pensively gazing at the floor, Ringo sitting quietly, Jane Asher backstage. These must have been hard to come by and satisfying when you captured them. Were you thinking about this ahead of time or were they spontaneous?

PM: Taking photographs, I’d just be looking for a shot. I’d aim the camera and just sort of see where I liked it. And invariably I’d pretty much just take one picture. We were moving fast, so I learned to take pictures quickly.

DH: There are some fabulous colour pictures from Miami that look like they were shot on bright Kodachrome film. Any serious photography at that time was made in black and white. The powerful effect of William Eggleston and Stephen Shore hadn’t yet appeared on the art scene. Why the switch to colour when you had been working in black and white?

PM: I just changed the film. We used Kodak 400ASA for the black and white stuff, and then we moved to Ektachrome or Kodachrome for the colour stuff. You had to learn to load it and put it in a paper bag or under a coat or something, because you’d seen the press guys and the professional photographers do this.

Miami was a burst of colour. It was an exciting place to be. When we went to these warm weather places, coming from Britain where you didn’t get an awful lot of that even in the summer, it was so exciting to be able to take some time off our punishing routine, to actually just sit down, have a day off, be by the pool, have a drink, cigarette, and sit around.

The colour pictures start happening when we get to Miami, and I like that aspect of the selection because it’s like we were living in a black and white world on the rest of the tour and suddenly we’re in Wonderland: Florida, the sun, the swimming pools, etcetera.

DH: How did you come upon the title Eyes of the Storm?

PM: I initially thought of Eye Of The Storm, singular, because The Beatles were in the eye of their own self-made storm, but as we looked at the pictures, I thought it’s more ‘eyes’ of the storm, because there wasn’t just one moment. There were plenty of moments when we were at the centre of a storm. And also, there were lots of eyes in the pictures of people. It was a crazy storm, a whirlwind, that we were living through, touring and working pretty much every day and seeing loads of people wanting to photograph us. So there were loads of eyes and cameras at the centre of this storm.

DH: In your foreword, you state that, ‘In looking back at these photographs, I have even greater regard for the photographers around The Beatles back then.’ Harry Benson, Curt Gunther, Dezo Hoffman, and Robert Freeman, all travelled with you and appear in some of your pictures. What was your daily interaction with them like? Did you learn from them as photographers?

PM: The great thing about having these photographers around was that they often just wanted us to ignore them. So, it was pretty easy for us! But in many ways, we didn’t ignore them. We saw what they were doing and we were interested. We noticed patterns and the setups they used and we asked questions. That’s how we came to understand things like newspaper columns — a photographer would get us to stand so we were sort of stacked on top of each other. We found out this was because the photo would then fit into a one-column space on the page. So we learned these tricks from them, and you’d get to spend a fair bit of time together too, so you’d build up a friendly rapport and they’d share the trade secrets.

They would also show us their ‘real’ photographs. Many of them did the newspaper work to pay the bills, but they would also have personal projects they’d be working on. They’d share those with us, so we started to understand what made for a ‘commercial’ photograph and what was more of an ‘art’ photograph. That ended up informing some of the photos we did later on in our career when we got to experiment more with our image.

Out of the list, we especially got to know Robert Freeman well. He came over to America with us and features in some of the photos in the exhibition and book. Robert was closer in age to us and we had a lot of shared interests. He ended up working with us on a few of our album covers and encouraged what I like to refer to as the ‘happy accidents’. This is when something happens by accident but makes everything more interesting.

To give you one story, we would sit together in a darkened room to pick the cover image for a new album and Robert would project different options onto a white board a few metres in front of us. We hadn’t done that before, but it was a great way to do it. I remember one instance where we were looking through the options for what became Rubber Soul and the board slipped a little so the photo got distorted, sort of elongated. We all looked at it and said — ‘That’s the shot!’ LSD had started to come onto the scene, and this trippy distorted image fit the time perfectly.

But that’s how we worked — we were always looking for a new way of doing something. We did the same thing in the recording studio. We would ask George Martin or the engineers almost childlike questions: ‘What does this do?’ Because that would lead to the natural follow up, ‘Can we try it this way instead?’

DH: Given your love of photography, and of course the influence of Linda’s work and presence in your life, did you pick up the camera again at other stages in your life and creative journey?

PM: To be honest, I’ve never really put the camera down. I’ve moved through different formats over the years, from film in the 60s to Polaroid in the 70s to a watch camera in the 00s. All the photography for my Driving Rain album was taken on a Casio wristwatch which had its own built-in digital camera. Now, I’m mostly on my iPhone, but the sensibility hasn’t ever really changed.

I mention this in the book, but someone on my team pointed out to me that I’ll sometimes sit in a meeting and, without really thinking about it, start framing up an image with my fingers, just because something in the room will have caught my eye. I’m a visual person. I have a form of synaesthesia in that I think of certain things in colours. Days of the week, for example. Growing up, I used to think of Monday as being black, because you had to go back to school! Friday was jolly and red. I paint too. With all art forms, I think once you learn how to ‘see’ — as in how John Berger would define ‘seeing’ or how Hazel [Larsen] Archer taught Linda to ‘see’ — I don’t think you ever really stop thinking about it.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.