Saturday, November 15, 1969

Interview for RollingStone

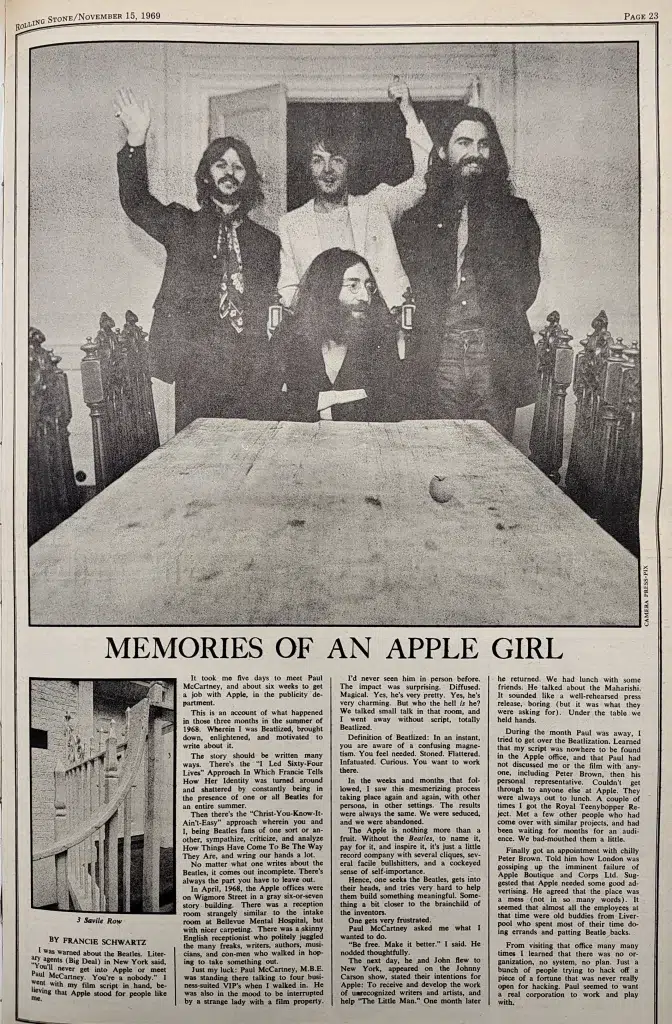

Memories of an Apple girl

Press article • Interview of Francie Schwartz

Saturday, November 15, 1969

Press article • Interview of Francie Schwartz

Session November 6-7, 1969 • Recording "Stardust"

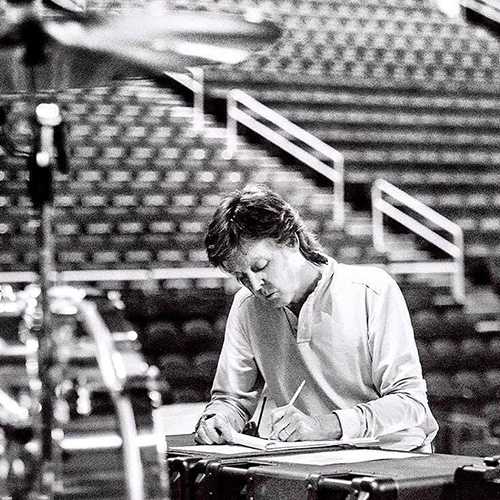

Interview Nov 07, 1969 • Paul McCartney interview for Life Magazine

Interview Nov 15, 1969 • Francie Schwartz interview for RollingStone

Article December 1969 • The Beatles reject offers to perform live

Next interview Apr 09, 1970 • Paul McCartney interview for Apple Records

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

Francie Schwartz, born in 1944, is an American scriptwriter. In 1968, she engaged in a romantic relationship with Paul McCartney, which resulted in the end of his four-year engagement with Jane Asher.

Known to Paul as “Frannie” or “Clancy,” Francie Schwartz penned an autobiography titled “Bodycount,” released in 1972, chronicling her time with him, among other stories.

In November 1969, she wrote a 4-page article for Rolling Stone, when she talked about Apple Corps and touched on her relationship with Paul.

I was warned about the Beatles. Literary agents (Big Deal) in New York said, “You’ll never get into Apple or meet Paul McCartney. You’re a nobody.” I went with my film script in hand, believing that Apple stood for people like me.

It took me five days to meet Paul McCartney, and about six weeks to get a job with Apple, in the publicity department.

This is an account of what happened in those three months in the summer of 1968. Wherein I was Beatlized, brought down, enlightened, and motivated to write about it.

The story should be written many ways. There’s the “I Led Sixty-Four Lives” Approach In Which Francie Tells How Her Identity was turned around and shattered by constantly being in the presence of one or all Beatles for an entire summer.

Then there’s the “Christ-You-Know-It-Ain’t-Easy” approach wherein you and I, being Beatles fans of one sort or another, sympathize, criticize, and analyze How Things Have Come To Be The Way They Are, and wring our hands a lot.

No matter what one writes about the Beatles, it comes out incomplete. There’s always the part you have to leave out.

In April, 1968, the Apple offices were on Wigmore Street in a gray six-or-seven story building. There was a reception room strangely similar to the intake room at Bellevue Mental Hospital, but with nicer carpeting. There was a skinny English receptionist who politely juggled the many freaks, writers, authors, musicians, and con-men who walked in hoping to take something out.

Just my luck: Paul McCartney, M.B.E. was standing there talking to four business-suited VIP’s when I walked in. He was also in the mood to be interrupted by a strange lady with a film property.

I’d never seen him in person before. The impact was surprising. Diffused. Magical. Yes, he’s very pretty. Yes, he’s very charming. But who the hell is he? We talked small talk in that room, and I went away without script, totally Beatlized.

Definition of Beatlized: In an instant, you are aware of a confusing magnetism. You feel needed. Stoned. Flattered. Infatuated. Curious. You want to work there.

In the weeks and months that followed, I saw this mesmerizing process taking place again and again, with other persons, in other settings. The results were always the same. We were seduced, and we were abandoned.

The Apple is nothing more than a fruit. Without the Beatles, to name it, pay for it, and inspire it, it’s just a little record company with several cliques, several facile bullshitters, and a cockeyed sense of self-importance.

Hence, one seeks the Beatles, gets into their heads, and tries very hard to help them build something meaningful. Something a bit closer to the brainchild of the inventors.

One gets very frustrated.

Paul McCartney asked me what I wanted to do.

“Be free. Make it better.” I said. He nodded thoughtfully.

The next day, he and John flew to New York, appeared on the Johnny Carson show, stated their intentions for Apple: To receive and develop the work of unrecognized writers and artists, and help “The Little Man.” One month later he returned. We had lunch with some friends. He talked about the Maharishi. It sounded like a well-rehearsed press release, boring (but it was what they were asking for). Under the table we held hands.

During the month Paul was away, I tried to get over the Beatlization. Learned that my script was nowhere to be found in the Apple office, and that Paul had not discussed me or the film with anyone, including Peter Brown, then his personal representative. Couldn’t get through to anyone else at Apple. They were always out to lunch. A couple of times I got the Royal Teenybopper Reject. Met a few other people who had come over with similar projects, and had been waiting for months for an audience. We bad-mouthed them a little.

Finally got an appointment with chilly Peter Brown. Told him how London was gossiping up the imminent failure of Apple Boutique and Corps Ltd. Suggested that Apple needed some good advertising. He agreed that the place was a mess (not in so many words). It seemed that almost all the employees at that time were old buddies from Liverpool who spent most of their time doing errands and patting Beatle backs.

From visiting that office many many times I learned that there was no organization, no system, no plan. Just a bunch of people trying to hack off a piece of a fortune that was never really open for hacking. Paul seemed to want a real corporation to work and play with.

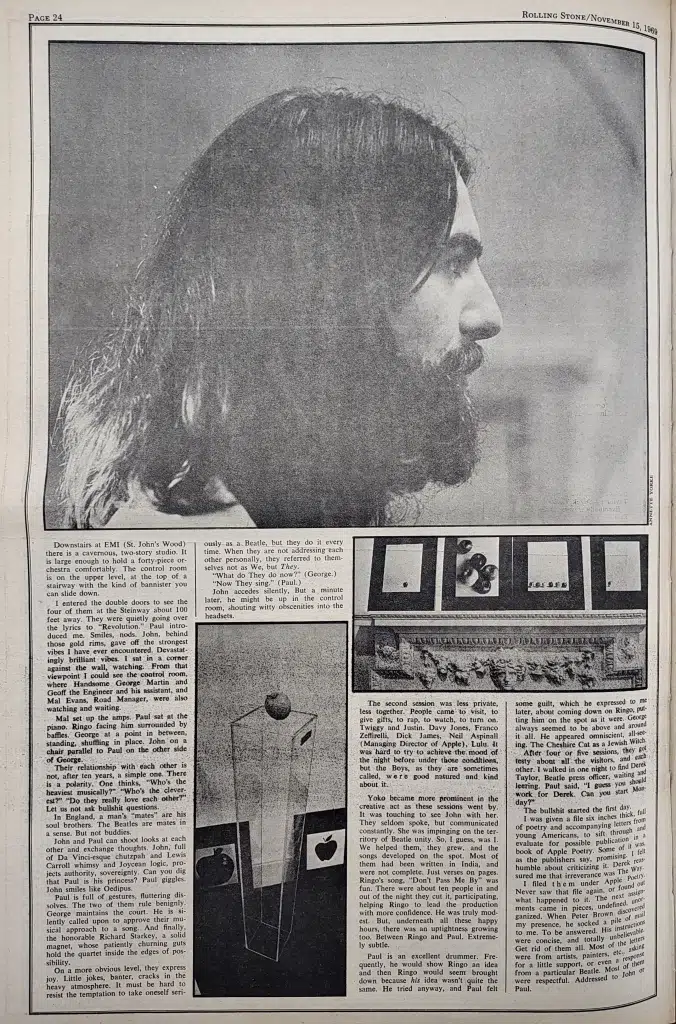

Downstairs at EMI (St. John’s Wood) there is a cavernous, two-story studio. It is large enough to hold a forty-piece orchestra comfortably. The control room is on the upper level, at the top of a stairway with the kind of bannister you can slide down.

I entered the double doors to see the four of them at the Steinway about 100 feet away. They were quietly going over the lyrics to “Revolution.” Paul introduced me. Smiles, nods. John, behind those gold rims, gave off the strongest vibes I have ever encountered. Devastatingly brilliant vibes. I sat in a comer against the wall, watching. From that viewpoint I could see the control room, where Handsome George Martin and Geoff the Engineer and his assistant, and Mal Evans, Road Manager, were also watching and waiting.

Mal set up the amps. Paul sat at the piano. Ringo facing him surrounded by baffles. George at a point in between, standing, shuffling in place. John on a chair parallel to Paul on the other side of George.

Their relationship with each other is not, after ten years, a simple one. There is a polarity. One thinks, “Who’s the heaviest musically?” “Who’s the cleverest?” “Do they really love each other?” Let us not ask bullshit questions.

In England, a man’s “mates” are his soul brothers. The Beatles are mates in a sense. But not buddies.

John and Paul can shoot looks at each other and exchange thoughts. John, full of Da Vinci-esque chutzpah and Lewis Carroll whimsy and Joycean logic, projects authority, sovereignty. Can you dig that Paul is his princess? Paul giggles. John smiles like Oedipus.

Paul is full of gestures, fluttering dissolves. The two of them rule benignly. George maintains the court. He is silently called upon to approve their musical approach to a song. And finally, the honorable Richard Starkey, a solid magnet, whose patiently churning guts hold the quartet inside the edges of possibility.

On a more obvious level, they express joy. Little jokes, banter, cracks in the heavy atmosphere. It must be hard to resist the temptation to take oneself seriously as a Beatle, but they do it every time. When they are not addressing each other personally, they referred to themselves not as We, but They.

“What do They do now?” (George.)

“Now They sing.” (Paul.)

John accedes silently, But a minute later, he might be up in the control room, shouting witty obscenities into the headsets.

The second session was less private, less together. People came to visit, to give gifts, to rap, to watch, to turn on. Twiggy and Justin. Davy Jones, Franco Zeffirelli, Dick James, Neil Aspinall (Managing Director of Apple), Lulu. It was hard to try to achieve the mood of the night before under those conditions, but the Boys, as they are sometimes called, were good natured and kind about it.

Yoko became more prominent in the creative act as these sessions went by. It was touching to see John with her. They seldom spoke, but communicated constantly. She was impinging on the territory of Beatle unity. So, I guess, was I. We helped them, they grew, and the songs developed on the spot. Most of them had been written in India, and were not complete. Just verses on pages. Ringo’s song, “Don’t Pass Me By” was fun. There were about ten people in and out of the night they cut it, participating, helping Ringo to lead the production with more confidence. He was truly modest. But, underneath all these happy hours, there was an uptightness growing too. Between Ringo and Paul. Extremely subtle.

Paul is an excellent drummer. Frequently, he would show Ringo an idea and then Ringo would seem brought down because his idea wasn’t quite the same. He tried anyway, and Paul felt some guilt, which he expressed to me later, about coming down on Ringo, putting him on the spot as it were. George always seemed to be above and around it all. He appeared omniscient, all-seeing. The Cheshire Cat as a Jewish Witch.

After four or five sessions, they got testy about all the visitors, and each other. I walked in one night to find Derek Taylor, Beatle press officer, waiting leering. Paul said, “I guess you work for Derek. Can you start Monday?”

The bullshit started the first day.

I was given a file six inches thick, full of poetry and accompanying letters from young Americans, to sift through and evaluate for possible publication in a book of Apple Poetry. Some of it was, as the publishers say, promising. I felt humble about criticizing it. Derek reassured me that irreverence was The Way.

I filed them under Apple Poetry. Never saw that file again, or found out what happened to it. The next assignments came in pieces, undefined, unorganized. When Peter Brown discovered my presence, he socked a pile of mail to me. To be answered. His instructions were concise, and totally unbelievable. Get rid of them all. Most of the letters were from artists, painters, etc., asking for a little support, or even a response from a particular Beatle. Most of them were respectful. Addressed to John or Paul.

After reading about 50 of them, I came across some very exciting slides of illustrations along Rousseau-ish lines. I took them into Peter Brown and told him I thought we should send the guy some bread, commission him to do a cover for one of the Apple artists. He coolly instructed me to write a polite rejection letter. His instructions were the same for all the Little People.

You have to be disgusted behind a thing like that.

I complained to Derek Taylor, who was, for the most part, sleeping late, or at some kind of press club affair. He reassured me that I was indeed working for him, and not for Peter, and gave me another assignment. He told me to mention the rejection bit to Paul.

In the meantime, I did not have a work permit, and was trying to find someone in the office to write the necessary letter to the Ministry of Foreign Labor, which does not dispense work permits easily. Derek kept saying he’d do it, but didn’t. Peter Asher wouldn’t do it. And Neil Aspinall made it clear he didn’t think I was important enough to merit that much effort on the part of Apple. “Think of the musicians, Fran.”

I told him, as confidently as I could, that Paul had hired me and Derek wanted me around. He halfway acceded after weeks of nagging. Condescended to slip me a lousy 12 pounds ($28.80) a week out of petty cash.

Derek’s new assignment was James Taylor. When James arrived, sweaty and angular, there were no meetings or interviews set up. James played for the new LP. He seemed apprehensive, but never openly expressed it.

I was to write his “bio,” which in the record biz means a cleverly written biography which is sent out as publicity and information. Spent several good days with him, walking in the streets, scouting photography locations, good-rapping the Beatles, trying to get it on. No one at Apple ever seemed to know when his pictures were going to be taken or by whom, and James just good-naturedly went along with it, because he wanted his LP and had faith. He told me a fascinating life story. I wrote a good bio. A year later I saw a copy of it in the ad agency for Capitol. It said “James Taylor by Derek Taylor.”

Eventually James came over to the Beatle sessions and played the guitar a little. Paul was his usual obscure and charming self. When James finally started recording with Peter Asher producing and Paul to help, the sound that came out was lush, and I thought over-produced. Even James’ tastes. But there it was.

By this time, I had been working for Apple three weeks and I was exhausted. Several Apple employees who shall re-main unnamed were totally useless, collecting fat salaries by virtue of reputation and hype. One could see that the Beatles were being taken.

Perfect example: Wonderwall cover. Somebody told somebody that a certain New York art director could do a knock-out cover, so they paid a man 200 guineas, which is like 600 dollars, and he did a very safe cover. When Paul showed it to me, I said I thought it had no balls. He didn’t understand what I meant by that. It was slightly altered. Then George brought in the Berlin wall shot, and someone else brought in another idea, and the cover never really got together at all. No one could assemble the Committee to agree on it. By the time the job was printed it was too late to make any changes anyway. So then John and Yoko and Paul and I sat down and said, “For God’s sake why doesn’t this company have a good advertising agency?” I explained to the best of my ability what a good agency can do.

“Go find one,” said Paul. He neglected to mention that he wasn’t willing to pay for a speculative campaign. Of course, no decent ad agency will do one for nothing. So I traipsed all over the tourist-ridden city of London, and found two young men at Doyle Dane Bernbach who had eyes to start their own shop, and were willing to give it a try. They attempted an ad for the first Apple releases (“Hey Jude,” “Those Were The Days,” “Sour Milk Sea,” “Thingumybob,” etc.) but had a hard time doing it. Repeatedly given insufficient or unclear information, they got uptight, and came to the point of having the “fuck-it” look in their eyes.

Next: Paul felt it was time for a photo session. The fan club people had been screaming for some new Beatle pix. The Beatles felt that any photographer in London would be honored to shoot them. (At least Paul said that.) Cecil Beaton offered his services, but George didn’t dig it, so no go. Besides, said Peter Brownnose, Beaton’s shots would be “too good” for the fans. I cringed, and began searching for a hip photographer. Jeremy Banks helped. Liverpool’s fan club sent props. Hired a van and some costumes, and scouted locations.

Of course, on the appointed day, the Beatles could not be gotten out of bed on time, and what was supposed to be a three-hour session took all day. But it was all right.

Yoko and I stood just outside of camera range and watched them standing among the hollyhocks. We saw them climb the ruins of an old subway station, and wince against the dusty air coming out of the half-assed wind machine in the photographer’s studio. I forgot that photographer’s name, but he was no Avedon. The Beatles, more specifically Paul, demand greatness in return for greatness. That’s when they trip themselves.

Some of the best shots of the day were the ones Yoko took with her Instamatic.

When that period of activities blew over, we moved to Savile Row. A million dollar townhouse. Faggoty apple green carpeting with wallboard partitions on top. Neo-Chinese Restaurant wallpaper. Blech.

In Derek Taylor’s office (three rooms on the third floor), Beatle photos, original writing, and records were lumped in dusty cartons like corpses, with old sneakers and fan mail and junk in the corners. One waited for Beatle orders to come through on the single phone.

The workers were suspicious and irritable, what with the constant rain and bullshit. I became a crusading reformer, at least in my mind. The message I got in return from several of my co-workers was, “I’m closer to Them than you’ll ever be, so watch your step, bitch.” Behind these petty go-rounds there was fear. Fear of trading on Beatle toes. Fear that somehow the money would run out, and we’d all be in the street.

It was disheartening to see these people, incapable of performing a creative job, playing games with a vengeance.

Yoko upset the cart a few times too, especially when she walked into the office to make suggestions. She too encountered the office politics. When she and John merged, he kindly offered to pay her old debts. The Apple Accountant (it sounds like something out of Orwell) screwed up his little mouth and balked.

Derek was more tactful. It was his responsibility to keep the press painlessly unaware of the John-Yoko thing, at least until the divorce could be negotiated.

Derek Taylor quit a lot. And was fired a lot. I was caught in the middle of it, because of my undefinably close relationship with Paul, and my professional allegiance to Derek (sometimes I think professional allegiance is bullshit too… a buddy system). In the morning Derek would ask me what Paul was up to the night before at the studio, and in the evening Paul would ask me what Derek had been up to at the office; was he doing the job and all that. A person gets nervous in that service.

So why didn’t you quit right then and there, you ask? Answer: One contemplates life without the daily presence of Beatles, and it’s a boring fantasy. One tries to hang in there, and try to make the dream of happy Apple-ness a reality.

There were pleasant breaks in the drudgery. Yellow Submarine (watching Paul watching the cartoon of himself on color TV… a gas). The funny breakfast at the Ritz with the Biggies from Capitol (no ties, but we made it anyway). The moment at Trident Studios when “Hey Jude” was finally finished.

The song had begun one afternoon when Paul went up to Weybridge to visit Cynthia Lennon and Julian, I think. He sang the first verse to George at the EMI Studios the night after. Several weeks later, some forty old brass players sat in the pit-like Trident Studios, and sang “Na na na nanana na… Hey Jude.” When Paul played the finished tape, he turned out the lights. The whole room seemed to melt into the song. After it was over he said he still “couldn’t hear it.”

It is a great song. I think of it as something he wrote partly to himself. Paul telling Paul to accept himself and the people who loved him in that summer of turmoil. Paul telling Julian Lennon that his daddy still loved him.

Ringo Star loves his wife and children. They are his favorite topic. He didn’t dig the uptightness that was developing in the studio or at the office. It happened one warm evening when John was supposed to come up to Paul’s house and write. Ringo quietly walked up the two flights of stairs to Paul’s little studio, and said “I don’t want to drum any more.”

Paul listened gravely, while Richard (that’s what Maureen calls him) explained that he didn’t get any pleasure from drumming any more. He nodded while Ringo talked about how much fun it was to act in the movies. He nodded when Ringo said he missed doing concerts, and loonin’ about. He looked chagrined when Richard complained that Paul never came to visit him in Weybridge.

I went down and made some tea. When I finally made it up the stairs again Paul was in the middle of saying, with a slight touch of humor in his voice, that it would sound pretty funny to announce the group as “John, Paul, George and Barry…” He reassured Ringo that he too was feeling bad about what had been happening at the studio. And that there was a lot of guilt connected with his slightly authoritarian drumming suggestions. Most of all, Paul expressed a desire to be more open, to level with Richard.

The talks ended shortly, Paul saying We Need You, and suggesting that they stop recording for a few days, to give Richard a chance to reconsider.

All was as well as it ever can be the following week, then Ringo returned to a Welcome Back Party of sorts. It would be October before they finished an LP full of inconsistencies and uncertainties. At least it was released and sold. They talked about inserting a book like Playbill with beautiful camp photos and typographic stars (In Order of Appearance) as if the LP was a show, a stage show. A similar concept had evolved with Sergeant Pepper… but alas, it never happened.

So many things never happened.

The big thing that never happened: the hiring of a superman. Paul kept mentioning that he would pay a fortune to the right executive genius, to put Apple in working order. The Beatles aren’t dummies. Idealists, yes: Nevertheless, they possess a clear-eyed sense of Finders-Keepers. Had a superman presented himself at the door, they could have used him intelligently.

They were well aware of the uselessness of many of their employee-buddies. They even tried to realign the responsibilities so that the back-pedaling could be minimized. But the biggest chair of them all remained eerily vacant.

Management Placement Services were suggested to them. They rejected this alternative as too impersonal or something. Maybe they thought the guy would come to them on a flaming gold disc. I don’t know.

It was hard to accept such an obvious lack of judgement along with their determinedly individual life-styles.

[PAUL MCCARTNEY’S HOUSE]

St. John’s Wood compares favorably to Olde Beverly Hills. The house on Cavendish Avenue is over two hundred years old, and stands a Stone’s throw from Lord’s Cricket Ground. On Sundays you can hear the polite crackle of applause.

It is surrounded by an eight foot brick wall. There is a double gate, the same height, of black wood, with a heavy guage metal screen over it. The creamcolored posts on either side of the gate are covered with pencil and felt-tip graffiti — “Mick Jagger’s cock is bigger than all four Beatles put together!” — “The Word is — Paul” — “I was here for ten hours last night, but I love you anyway” — “Paul favors Americans!” Etc.

The parking area in front is concrete, from whose cracks spring pale green wildflowers. A giant oak, it’s limbs outstretched, shades half the area. It smells good.

The tall front door is painted black, with an old brass knob in the middle. The entry hall leading to the living room is carpeted in a deep teal blue, with Persian and Indian scatter rugs here and there. The ceiling is very high, with baroque molding around the edges. The couch and chair that face the fireplace are forest green velvet with mahogany carvings and many paw-prints. There is a big rip in the side of the couch. Three kittens poked their heads out, demanding food and attention all summer. There’s a simple coffee table covered with cheap madras cloth sent by a fan. The phones, one white, one biege, sit by the Daddy-chair. The circle where the numbers should be is blank.

There are three Magritte paintings. The one over the mantle is an ominous dark composition with only a small monastic window showing sky. The right half of the picture is filled by a figure that resembles a dead fish, but on closer perusal, looks monkish. A smaller painting on another wall is the proverbial apple with the legend “Au Revoir” across its middle.

A primitive portrait of Khrushchev, a tiger scroll from Japan, a little framed picture of Julian Lennon embroidered on muslin. Portrait of Paul in charcoal, laboriously but lovingly done by an American fan.

On the wall opposite the fireplace, some fifty feet away, are shelves. Reading from left to right, hundreds of LP’s, (Elvis, Sam and Dave, Lenny Bruce, Beatles, the debonaire Fred Buchanan, Dionne Warwick, Bulgarian Folk Chorus), knick-knacks from India and America, a black and white TV set with a tape monitor, and a couple hundred books (he didn’t read much when I was around, but how could he?) A tuner, turntable, and speakers are built in. On the floor nearby, a basket of fan mail, packages. An old desk stuffed with papers and precious mementos. It was here that Paul wrote notes to the old woman across the street, who wrote to him in a palsied hand of her illness, and distress at the noise the groupies were making outside.

In the middle of the wall that faces the garden, there is a door. The bottom half swings open for Martha’s galumphing entrances and exits. Little Yorke Eddie wasn’t strong enough to get through it, but tried, and whined. Ended up pissing all over the carpets. Paul didn’t mind. But then he didn’t have to clean it up.

The garden, at least 125 feet deep, is uncut, and wild. The grass and a few wildflowers, weeds, are at least a foot deep in some places. You can see the stone Alice in Wonderland figures on the cover of “The Ballad of John and Yoko.”

He has a hip gardener, who is teaching him bit by bit, about each of the plants in the yard. When he’s alone, he goes out to romp with Martha, fondles a branch or two. In the very back, there’s a small building, unfinished as of ’68, that was built originally for meditation. It’s glass on three sides. Indirect lighting. In the middle is a circular platform on a hydraulic lift. At the push of a button, the center of the platform rises up into a glass dome. Once Paul wistfully said to me that when he conceived the building, he meant it to be a place where no words were spoken. There was a note of irony in his voice when he carried a rug out to the platform, and Martha and I climbed up with him to rise into the dome and look at the stars and lacy trees that pierce the sky in the glass. This was the location of some of the Life Magazine photos.

The remainder of the first floor in the main house is a McCartneyesque kitchen with strong Jane Asher influence. Spice racks of apothecary jars. Pristine white plates displayed on open shelves, plenty of butcher-block counter space, and some revolving cupboards which Paul designed himself.

In the middle of the foyer, the stairwell goes up two flights. A perfectly simple light fixture hangs down from the very top. Well traveled stairs lead to the second floor landing, where there are two doors to the master bedroom, converted from two to one when Jane and Paul first took the house. White walls, a fireplace. Deep red velvet curtains over sheer white. A counter along the front wall, with an electric vanity in the middle. The rest of that wall, below the counters, is drawers; sweaters, more sweaters, clothes and trays from India, the hair-drier that Paul uses. On the counter, a small stuffed dragon, a plate full of buttons, keys.

The tie rack is on the back of the door, slung haphazardly with wide brilliant ties. Rusty orange carpeting. The bed on the opposite wall is big enough to sleep three. The closet by its side holds 30 or more suits and piles of shoes. A switch panel next to the bed controls the lights, draws the curtains. Behind the hall on which the headboard is mounted, is another closet. Inside is a safe full of papers, and a checkbook that Paul hasn’t used in years.

The bathroom, whose window has a small balcony outside it, faces the front courtyard. It is beautifully laid with russet and white patterned tiles, and the wall inside the shower-bath, which has no door or curtain, is mirrored. (There is a tiny view of this bathroom in one of the pictures on the poster that came with The Beatles.)

There are two more bathrooms and a smaller bedroom on this floor. Sometimes Michael (McGear – McCartney) sleeps there. In the bathroom that overlooks the back yard, Paul could be found, silting on the window ledge shaving, gazing outward, ignoring the phones. A morning’s escape.

On the third floor there are three more small bedrooms, and Paul’s studio with multi-colored spinel, sitars, tape recorder, and sculptures. It too faces the front, and on several summer nights he sat playing and crooning, to himself, and to the groupies outside. The dogs curl around his feet and sleep while he’s at it.

John and Yoko were up there in the wee hours, playing their tapes, and the newly minted Beatle songs. It’s the warmest room in the house. There’s a notebook of hew songs sitting on the piano, and tapes of Paul doing old Pepper songs in the tape cabinet.

All in all, it is a slightly unkempt but charming millionaire’s home, well-used, oft-trampled, but always with a nostalgic aura of the times when he first had money to spend. He will probably always keep it, and hopefully fill it with little children. The dogs never quite made it as substitute offspring, but they were awfully nice to have around when things got lonely for him. He took great delight in watching them frolic after a long session at the studio.

Lots of teenyboppers and ardent fans got into the yard or the house during the summer. It’s not impregnable. But they all seemed a little sheepish when they were caught. When a person cares that much for a “star” they have to respect the times when he wants a little solitude.

Even when they irritated him, he was never hasty or mean. In fact when a neighbor would call the police to disperse a particularly noisy bunch, he would peek through the curtains a half hour later to see if they had come back. He wasn’t unhappy when they did.

Sometimes he took his breakfast (1 PM) on the back porch, on a wooden picnic table and chairs. And there were a few rare days when Paul could lie in the beach chair with his eyes closed and catch a little sun before leaving for the office.

He always felt an obligation to go to the office, no matter how tired, or occupied with various problems, he was. To say that any Beatle is lazy would be ludicrous. Even fun-times were interspersed with talk about the Apple situation.

Spending free time with Paul was a precious private thing. It also helped me to understand the bond between him and John.

One afternoon we drove to the countryside to visit Derek Taylor and family. It was pouring rain, wind swishing through leaves. Paul and Martha (Dear Sheepdog) led Derek’s children in a procession around the little lake in back of the house.

We sat and listened to “The Beatles Story,” a documentary pseudo-Murrow collector’s item made during the peaks of Beatlemania. Paul had never heard it before. His face went “WOW.” (There is one cut of a young girl, crying, on the edge of hysteria about how great, how personally touching the Beatles are … an orgasm of tears.) He said that they had not been aware of that individual intensity. The Beatles, on stage at Hollywood Bowl, Shea Stadium, etc., did not hear the words coming from those Natural Wonder Mouths… They were too busy trying to hear themselves play, keep the beat.

I asked him when we were alone if he ever thought about the power he has to communicate a message to millions and millions everywhere. The power to move people. He silently shook his head; those puppy eyes were looking far off into the horizon. I couldn’t swallow his answer, but neither could I find a better way to ask the question. Does he really want to keep it cool and safe and frivolous?

As the summer in London wore on, more bad-raps about the Apple Boutique circulated. Paul, always the most agonized self-examiner, asked me to do a status report on the stores. I submitted it to Neil Aspinall, got a curt thank you, and a “good” from Paul.

Perhaps that effort led to the closing of the boutique. I wasn’t the first to suggest it. And the accountant could have easily done it better than I, who never saw the balance sheets.

Closing of the boutique was front page news in London. The give-away took some of the sting out of it. (Michael Pollard was among the freaks standing in line for free goodies.) The night before it closed, the four Beatles raided the place, and returned to Paul’s house with armfuls of charming clothes. Where they found them is still a mystery to me. Most of the merchandise in Baker Street reminded me of a psychedelic Woolworths.

One wants to write the truth. To write about the Beatles and their company with some degree of objectivity. Lyrics like “I feel hung up and I don’t know why” keep coming in, reminding me that at different times in my life, Beatle music has meant something big and important to me. It was always deeply personal, an inspiration, not a titillating opiate.

Three Savile Row is a lovely old house. When I worked there it became a multi-chamber of psycho-dramatic denouement, stuffed with juicy writing material. Include the following conditions: Dispassionate alienation, neurosis, fear, groveling intellectualism, and ultimately … bullshit.

We should know better than anyone else that the Beatles merit our good faith. And support. The Beatle product is still uniquely satisfying, to all levels of listening and interpretation. Nine-to-fivers who felt trapped by the water cooler turned on. The emancipation of many an over-30 is due directly to the universal appeal of John, Paul, George, and Ringo.

Keep this in mind when you read the minute and petty details of the Apple and its worms.

Give Peace a Chance.

Having been in the midst of their corporate Masturbation (No Sin Implied) l can feel for John when he says “Christ, you know it ain’t easy.”

Hearing staunch Beatle supporters sourly mutter, “They’re fucked,” one knows that something negative is and was happening. Perhaps the money had something to do with it.

The Beatles remain naive in many ways. Their wit and style does not preclude a tendency to be seduced by elaborate con-businessman.

Even in private, one never heard them praising Brian Epstein. Maybe they were too close to him to see what he really did. Their business trip was, and seems to be a bummer. People associated with them are confronted with the inconsistency, the farce, of playing a game in which the rules are undefined and the rule-makers are anti-rule, self-contradictory, a paradox.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.